The Kon-Tiki voyage led by Norwegian explorer Thor Heyerdahl was a huge success and proved beyond doubt that Polynesia could have been settled from South America.

One of the great mysteries of anthropology is how Polynesia – a vast pseudo-country in the Pacific spread triangularly between Rapa Nui, Hawaii and New Zealand – came to be inhabited by people with similar customs, cultures and, notably, languages.

Many theories

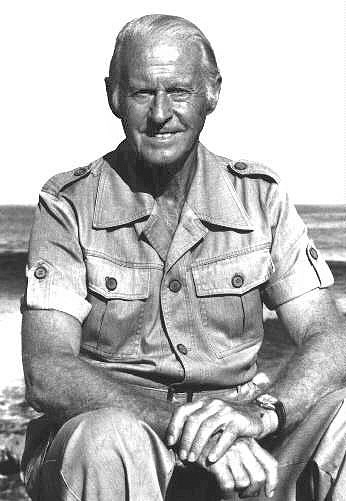

One theory, advanced in the 1930s is that the Islands were populated step-by-step from South-East Asia. But many remained unconvinced, including a Norwegian Explorer and Ethnographer by the name of Thor Heyerdahl.

Thor’s theory was that the islands making up Polynesia were settled from the West by natives of South America using ‘drift voyaging’ – basically building a raft with a sail and letting the ocean take you.

His primary evidence was the Moai statues on Rapa Nui (known in the West as Easter Island) which, he claimed, owed more to South American than Asian culture. There was also the legend of Kon-Tiki Viracocha, a native chief who is said to have set sail from Peru into the sunset on a balsawood raft.

When making these claims, Heyerdahl was dismissed by most anthropologists with one, Herbert Spinden, exclaiming ‘Sure, see how far you get yourself sailing from Peru to the South Pacific on a balsa Raft!’ Not one to turn down such a challenge, even though it wasn’t necessarily serious, Thor Heyerdahl decided to do just that.

The crew

Thor set about assembling a crew, each of which could bring a useful skill to the voyage. All had to be hardy and courageous – this was to be a long and treacherous voyage – and it wasn’t long before he’d found his team. In total, the six-man crew consisted of five Norwegians and one Swede.

Herman Watzinger was a thermodynamics engineer. He was in the US studying cooling technology when he met Thor Heyerdahl by chance. He asked if he could join the voyage and Thor agreed instantly, making him second in command. Throughout the voyage he gathered vast amounts of data, providing insights into this largely unstudied area of the ocean at the time.

Erik Hesselberg was a childhood friend of Thor’s who had, as a trained sailor, spent several years in the merchant navy. Thor made him the navigator on the voyage and, thanks to his arts education, was also the one who created the iconic Kon-Tiki image that adorned the raft’s sails.

Knut Haugland was a telegraph operator who, during World War II had participated in the Norwegian heavy water sabotage in 1943, one of the most successful acts of sabotage in the war, preventing the Germans from obtaining heavy water to use in nuclear weapons.

Torstein Raaby was also a wartime telegrapher who had successfully provided the Allies with information on German warships through tapping the German’s communications.

Bengt Danielsson was a Swedish Sociologist specialising in Human Migration Theory. Bengt served as steward, in charge of rations, as well as translator, being the only crew member who spoke Spanish.

Though remaining on dry land, Gerd Vold Hurum was the seventh, and perhaps most vital, member of the team. A code specialist from the Norwegian Embassy in Washington, she was the secretary of the expedition. Her role was to coordinate communications between Washington and the raft, which she could then pass on to Norway. At the end of the voyage she arranged for their repatriation and for the voyagers to meet with President Truman in the White House.

The voyage

The team travelled to Ecuador to secure a supply of balsa wood and then on to Peru where they built the raft. The raft carried around 1000 litres of drinking water in both ancient and modern containers – to prove that ancient storage was up to the task – and foods such as sweet potatoes and coconuts that would have been available to the ancient voyagers.

Thor also secured radio equipment and field rations from contacts in the US military.

Whilst the South Americans clearly wouldn’t have had such equipment, Thor argued that its presence wouldn’t disprove the theory that a raft could drift West to Polynesia unless its use proved vital to the journey. Notably, the hand-cranked generator meant that it wasn't exactly a luxury!

The team set sail on April 28th 1947, initially being towed by the Peruvian navy to avoid traffic close to the coast. They then rode the Humboldt Current and the trade winds, roughly due West.

On July 30th the team caught first sight of land – the atoll of Puka-Puka. 5 days later, after 97 days at sea, they reached the Angatau atoll where they made contact with the inhabiants but were unable to safely land the craft.

Two days later, on August 7th, the raft struck a reef and eventually beached on an uninhabited islet off the coast of Raroia atoll. After a few days, washed up flotsam from the raft alerted villagers nearby who then arrived on canoes to rescue the voyagers. They were taken to the nearby island and welcomed with traditional feasts and dances.

Shortly afterwards, they were taken to Tahiti by a French schooner, with the raft towed behind.

Kon-Tiki on the big screen

Like all sailors, especially ones with a point to prove, Thor made copious notes and logs along the journey. Most importantly, the crew had a single 16mm video camera, which they used to document the expedition.

The combination of this film, with stills and diagrams explaining the process of building the raft, forms the basis of the documentary Kon-Tiki. Released in 1950 in Norway and later in the US, the feature won best Documentary for 1951 in the at the 24th Academy Awards.

In 2012, a dramatization of the events was made into a film of the same name. This was Norway’s entry to consideration for the Academy Awards but despite making it through to the final five nominations for Best Foreign Language Film, it was beaten by Michael Haneke’s film Amour.

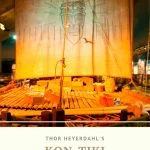

The Kon-Tiki museum in Oslo

Located in Oslo, the museum is a record of everything related to the expedition.

Read more: The Best Museums in Oslo

You can read the whole story and see photos of the crew along the way.

The Oscar-winning documentary of the voyage plays throughout the day. The crowning glory of the museum, however, is the original raft, which takes pride of place in the museum’s collection.

Kon-Tiki’s place in history

The Kon-Tiki voyage was a huge success and proved beyond doubt that Polynesia COULD have been settled from South America. It did, however, do nothing to prove that it was!

Read more: Norway's Kon-Tiki Museum To Return Artefacts

More recent advances in genetic testing and radiocarbon dating have shown that, whilst some South American origins are present in the Polynesian DNA pool, the vast majority is distinct.

There’s no conclusive proof of origin, and we still don’t know how and why the Moai on Rapa Nui got into place. But we do know, thanks to Thor Heyerdahl, that a South American influence is one possible explanation.

Did you enjoy this post? If so, why not share it on Pinterest so others can find it too? Just hit the social sharing buttons for the ideal pin.

I am pretty sure the picture at the top of the article is The Ra raft.

Further down is the picture of Kon-Tiki.

I loved the article.

Enjoyed the story of the KonTiki and visiting the museum in Oslo really is an interesting place to view the sailing vessel. It took great faith and courage for the men to construct and sail on a boat made of balsa wood. As a side note there is a museum in Alesund that has an original boat – The Uread – that sailed from Alesund to Massachusetts in 1904-1905 taking five months with the inventor and 3 others and you might find the story “Uread The Egg That Crossed the Atlantic”, as well as a visit to the Alesund Museum most interesting.

i love kon tiki

Ugh, the amount of grammatical errors in this article is just unbelievable!

I’m sure you’ll still steal it for your school project though!