Harald Hardrada ruled Norway from 1046 to 1066. Whichever way you spell his name, here is the story of the last great Viking ruler.

1066 was a major turning point in British history as Anglo-Saxon rule came to an end, to be replaced by the modern monarchy that persists to this day. For the Vikings in Norway, however, it was more than simply a turning point in history.

King Harald Hardrada, said by many to be the last great Viking ruler of Norway, met his demise and so the Viking Age was officially over. Like much of European history, these two seemingly unrelated facts are actually part of the same story.

You can view the story from the eyes of the British, though Harald was merely a supporting character in the Norman takeover of Britain.

Much better is to take a journey through the literal byzantine journey made by Harald, from a half-brother of Saint Olaf to a Norwegian king in his own right, and also a pretender to the British throne.

That's not my name

Before we delve too deeply let’s sort out Harald’s name. The name Hardrada is actually a nickname meaning something along the lines of ‘hard ruler’. The modern Norwegian form would be Hardråde or in the Old Norse Harðráði.

One scholar, Judith Jesch from the University of Nottingham, argues that Hardrada is ‘a bastard Anglicisation of the original epithet in an oblique case’ but still it endures. Further study suggests it might not be the best nickname to use anyway!

Other sources give versions of hárfagri – beautiful hair – as being Harald’s nickname. It’s possible that the nickname has fallen out of favour to avoid confusion with an earlier king known as Harald Fairhair. Perhaps Fairhair was the name Harald wished to be known by and it was his enemies who gave him the name Hardråde.

Either way, neither of those is his real name! Harald was the son of Sigurd Syr and so his real name would have been Harald Sigurdsson (Haraldr Sigurðarson in Old Norse). But as Harald is mostly known by his nickname, I’ll stick to that throughout to avoid confusion.

Also, along the way we’ll be meeting Harold Godwinson, an important but short-lived English King. Hopefully things won’t become too confusing – remember, Harald – Norwegian; Harold – English. Easy!

The early life of Harald

Harald was born in around 1015, to Åsta Gudbrandsdatter and her second husband, Sigurd Syr. His half-brother Olaf, later to become Saint Olaf, had just declared himself King of Norway and was setting about making that reality. The Youngest of three brothers, Harald was the only one who displayed ambitions beyond the family farm.

Harald and Olaf’s fathers are both said to be descended from Harald Fairhair, the legendary First King of Norway. Many scholars believe that Olaf may have been related to Harald Fairhair and Harald Hardrada probably wasn’t… but that’s a family matter!

Harald Fairhair united all of the fiefdoms of Norway, through alliances and military strength, into a country under single rule.

Growing up, Harald admired his half-brother Olaf, who in a few short years had managed to control more of Norway than anyone since Harald Fairhair. Both Olaf and Harald felt that uniting all of Norway was their calling.

So, Harald was most distressed when, in 1028, Olaf was deposed by Cnut The Great of Denmark and driven into exile in Kievan Rus.

In 1030, at the tender age of 15, Harald received the news that Olaf was on his way back. He gathered 600 men from around the Uplands and they travelled to meet Olaf on their arrival across the border from Sweden. Together they gathered an army and set about trying to regain the Norwegian throne.

The Battle of Stiklestad

According to the sagas of Sturluson, Olaf had amassed an army of by the time he crossed the mountains from Sweden and arrived in the valley of Verdal, about 50 miles North of the capital, Nidaros (now Trondheim).

Modern scholars doubt this and suggest that he may have gathered a rag tag bunch of robbers, bandits and miscreants but nothing like a large or useful army.

Either way, when they arrived at the Stiklestad farm in the lower end of the Verdal valley, they were met by an army of some 14,000 men led by Hárek of Tjøtta, Thorir Hund and Kálfr Árnason, the latter being one of Olaf’s ex-military leaders.

The battle did not go well for the half-brothers Olaf and Harald. Olaf was killed, possibly by the spear of Thorir Hund, and Harald was severely wonded. Olaf’s body was secretly taken away to be buried and Harald managed to escape.

The one saving grace was that, according to sources, Harald acquitted himself very well in the battle, showing considerable talent.

Escaping to Eastern Norway, with help from Rögnvald Brusason, Harald stayed at a remote farm to allow his wounds to heal. A month later he secretly travelled over the mountains to Sweden and, about a year after the battle, finally arrived in the relative safety of Kyivan Rus.

Exile to Kyivan Rus

Kyivan Rus, sometimes known as Ruthenia, was effectively what we might consider to be the North West corner of the Soviet Union. Today its lands are shared between Belarus, Ukraine, Poland, and Russia. The original Rus people are thought to have been Norse travellers, spreading out through the Baltic Sea.

Details of Harald’s time in exile are quite sparse. It’s likely he spent at least some of his time in the town of Staraya Ladoga, that is now part of the Leningrad Oblast. This was a popular trading outpost at the time and some consider it ‘the first capital of Russia’.

Harald and his men were greeted warmly by Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise and his wife Ingegard. Ingegard was a Swedish Princess and distant cousin of Harald’s. They had hosted Olaf during his time in exile there, and happily extended their hospitality to his increasingly notable half-brother.

Yaroslav was in great need of military leaders and so, recognising his relationship to Olaf and his similar qualities, made him a captain of his forces. It’s likely that Harald took part in campaigns against many people including the Poles, Chudes, Byzantines and Pechenegs.

After a couple of years helping Yaroslav in Kyivan Rus, Harald and his men set out to travel further South.

Making money in Miklagard

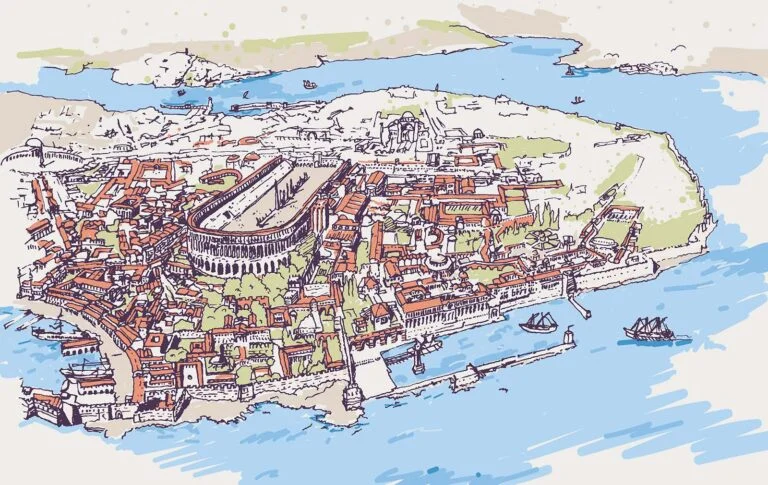

In around 1033 or 1034, Harald and his men arrived in Constantinople, capital of the Eastern Roman Empire, of the Byzantine Empire as it become known. The Norsemen knew it as Miklagard from Mikil meaning ‘big’ and Garðr meaning ‘wall’ – overall something like ‘stronghold’.

They joined up with the elite Varangian Guard, the Emperor’s personal bodyguard that was made up of men from Northern Europe, Scandinavia, and Britain.

This ensured that the guards were not tainted by local politics and rivalries and could be relied upon to deal with any threats or uprisings effectively.

Though some people claim that Harald was travelling incognito, most believe this would have been impossible.

News of military strength travelled faster than almost any other news during this time and so Harald’s exploits in Norway and Kyivan Rus would have been too well known for him to hide.

Harald and his men soon found themselves fighting all over, from the Mediterranean to the Tigris and Euphrates and all the way down to Jerusalem. Harald was very popular with the Emperor, Michael IV, and soon found himself the leader of the Varangian Guard.

Despite a small defeat in Sicily, Harald was called back to Constantinople and rewarded with titles from the Emperor. Unfortunately for Harald, Michael IV died and was succeeded by his nephew, Michael V, who didn’t trust Harald at all.

Harald was imprisoned, somehow managed to escape, and took a ship back up North.

Back to Rus

Harald’s first stop was Kyivan Rus where he once again met with Yaroslav the Wise. Harald had become very rich, thanks to being well rewarded for his services and also from plundering on his travels.

Sources tell of three times when he took part in ‘polutasvarf’ which translates as ‘palace plunder’, and would either have been literal plunder after the Emperor died or a huge payment from the new emperor to ensure good relations.

In Rus he married Yaroslav’s daughter Elisabeth (sometimes known as Ellisif). Harald supposedly asked to marry her on his first visit, when she would have been around 14, only to be rejected vecause he was not wealthy enough. Returning triumphantly, with great riches, he joined prominent royals such as Henry I of France, Andrew I of Hungary as a partner of one of Yaroslav’s children.

Not long after Harald arrived in Kyivan Rus, Yaroslav attacked Constantinople by sea. It’s likely that Harald provided information about the military there. They offered the chance to pay money or fight and the Byzantines chose to fight.

The Rus easily beat the Byzantine fleet but was then heavily damaged in a storm so returned to Kyivan Rus with nothing to show for their troubles.

Eventually Harald headed westward from Novgorod back to Staraya Ladoga where he purchased a ship. He sailed the rivers into the Baltic Sea and arrived back in Sweden around the end of 1045.

In his absence, the throne of Norway had been taken by one of his nephews, Magnus the Good, who had also managed to claim the Danish throne as well by defeating Sweyn Estridsson, the main pretender. Harald met up with Sweyn in Sweden, as well as the Swedish King, Anand Jacob and the three men set out to defeat Magnus together.

Claiming the throne

Their first act was to attack the Danish coast, in an effort to show that Magnus was either unable or unwilling to protect them. This was successful but Magnus, who was abroad at the time, heard of the attack and correctly assumed that the next target was Norway.

It’s likely Harald’s main plan was to claim the throne of his father’s previous petty kingdom and then claim the rest either by diplomacy or force. Instead, Magnus returned home and, on the word of his advisors, sought to build an alliance rather than engage in a war.

Each had something the other wanted so it wasn’t too difficult to come to an arrangement. Harald had vast wealth from his exploits abroad, while Magnus was effectively bankrupt. So, they agreed that Harald would be co-ruler of Norway, but not Denmark, while Magnus would hold the final say. In return. Harald would share half of his wealth with Magnus.

It’s said that during their co-rule, the two men kept very much to themselves and their only known meetings almost ended in violence! Fortunately for Harald, after less than a year, Magnus died. Depending on who you believe, he either fell overboard, fell off a horse, or fell ill and died of disease.

In a statement on his deathbed, Magnus made Harald his heir in Denmark and Sweyn his heir in Denmark. Thus, after 18 long years since Olaf was deposed, Harald ascended to his rightful place as the King of Norway.

During his reign he spent a lot of time and effort trying to gain control of Denmark from Sweyn until they eventually made peace in 1064

1066 and all that

And so, we come full circle to 1066 which, if you’re British, is approximately when history – at least what you get taught in school – begins. There were 4 pretenders to the throne when Edward the Confessor died.

Harold Godwinson, who was Edward’s brother-in-law, William of Normandy, who was Edward’s cousin, Edgar Atheling, who was an Anglo-Saxon Prince and Edward’s Great Nephew and Harald Hardrada who believed he was owed the throne through an agreement with Harthacnut, a previous Viking king of England.

Harold’s brother Tostig hated Harold and encouraged Harald Hardrada to come and claim the throne. Harald got a crew together and raided from the North of England. They initially succeeded at the Battle of Gate Fulford where he defeated the Earls Edwin and Morcar.

The men continued on, with only light armour as they were expecting no more than the easily crushed resistance they’d received so far. Unbeknown to them, Harold Godwinson and his army were already in the area and were preparing to repel the invading forces.

The two armies met at Stamford Bridge and clashed violently. Harald met his demise early in the battle as an arrow struck his throat. The rest of the men fought on but were ultimately defeated. They fled and returned to Norway.

Harold, meanwhile, didn’t have much time to revel in his victory as, shortly after, William attacked from Normandy. His men killed Harold at the Battle of Hastings and he became William I of England.

Good article. You guys are good Norwegians 🙂

This is a pretty good article, but left out a great deal towards the end.

Previous to the battle at Stamford Bridge, the Norse won the battle of Fulford Bridge and thought they were finished with heavy battle for the time being. They were caught by Harold when they were lightly armed making arrangements for ransoms, etc.

The other thing few seem to know about is that Harald’s body was retrieved a year after Hastings and brought back to Trondheim, where it rests under a side street and probably under a sewer line. The city authorities don’t want to dig him up to bury him amongst the other Kings in Nidaros cathedral!

William of Normandy was a descendant of the Viking (Norseman) Rollo. So as far as England the Norsemen still won in the end. England is technically still a Viking country. 😀

A nice idea but if ancestry of rulers determine a country’s national identity, England is probably currently German.