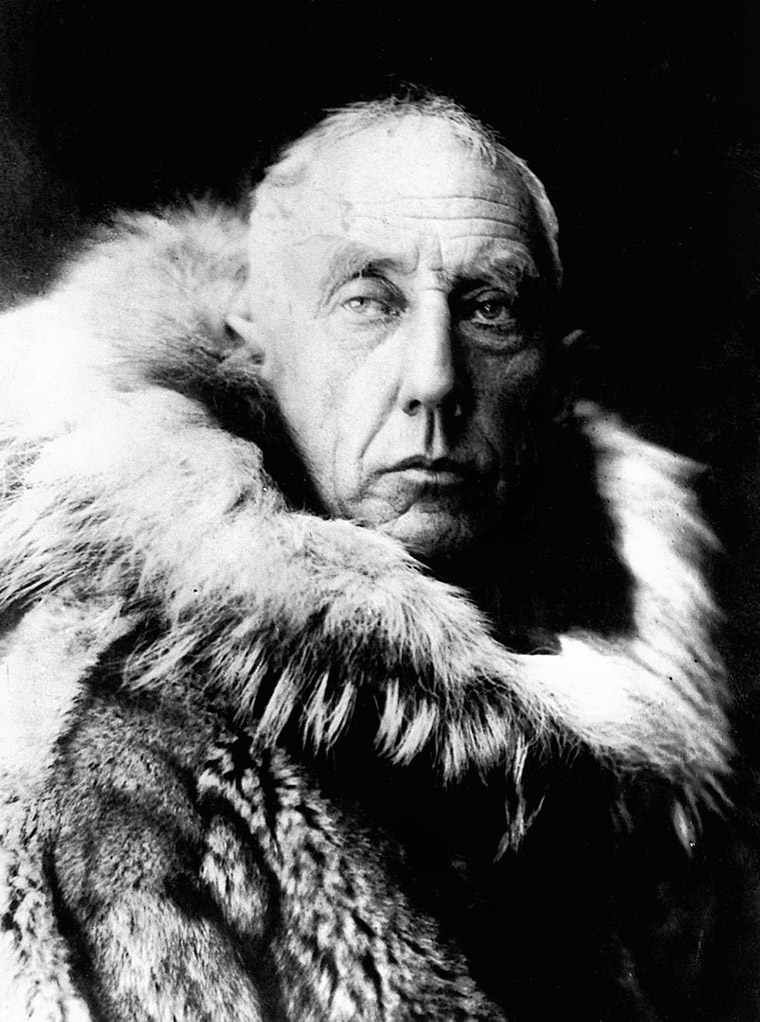

An introduction to Roald Amundsen, one of the most famous Norwegians to have ever lived. Discover some fascinating facts about the polar explorer.

Not every nation can boast a figure as well-known as Roald Amundsen, leader of the first successful expedition to the South Pole. At the age of fifteen, he was already captivated by Sir John Franklin’s narratives of his overland Arctic expeditions.

This fascination would lead him to the literal end of the world. His success in researching his expeditions, securing the necessary (often astronomical) financing and carrying them out is an example in determination.

One secret to his success is that he was eager to learn, both from his own mistakes and from others. For example, he learned local survival skills from the Inuit he met on one of his voyages.

Join us as we explore his work through these 11 fascinating facts about the life of Roald Amundsen, one of the world's most famous polar explorers.

1. He studied medicine

Roald Amundsen was originally destined for a career in medicine. He started his studies in the field in 1890, but after the death of both his parents, he decided to give up medicine and devote himself entirely to polar research.

2. His first polar trip was on a Belgian expedition

Amundsen’s first voyage was to Antarctica as a helmsman on a Belgian expedition under Adrien de Gerlache de Gomery from 1897 to 1899.

The expedition vessel Belgica got trapped in the ice near Peter I island, and drifted around in the Bellingshausen Sea all winter.

This meeting with the harsh realities of polar exploration proved a good school for Amundsen. He came out of the expedition even more determined to pursue a career as a polar explorer.

3. He looked for the fabled Northwest Passage

In the summer of 1903, Amundsen sailed out of Oslo (called Kristiania at the time) with a small ice-strengthened 45-ton vessel equipped with a 13 horsepower engine. The ship was named Gjøa, and the crew consisted of six men in addition to Amundsen himself.

One of the expedition’s goals was to sail the Northwest Passage: the shortcut between the Atlantic and the Pacific, via the Arctic Ocean. What made the Northwest passage so difficult to attain was that its waters were covered in ice most of the year.

Roald Amundsen’s ship was the first one to sail the passage in its entirety. It took him three years.

4. He proved that the magnetic north pole moves

Another goal of the Gjøa expedition was to establish the precise location of the magnetic north pole. This had already been done by James Clark Ross in 1831.

By finding the magnetic north pole again and proving that it was no longer in its 1831 location, Roald Amundsen proved that the pole was in fact moving. Since then, it has moved very fast indeed.

5. He spent two years with the Inuit

Because the measurements required to locate the magnetic north pole precisely would take time to carry out, Roald Amundsen looked for a suitable place to anchor his ship. He was delighted when he found the little cove now known in English as Gjoa Haven.

There were no people there when he arrived, but eventually the Netsilik, a local Inuit group, arrived. Both groups established a relationship that turned out to be mutually beneficial – especially for the Europeans.

The explorers received prepared reindeer skins as well as complete outfits of clothing, and the precious knowledge of how to build igloos. The Netsilik, on the other hand, received needles, knives, empty tin cans and other articles.

At the time, the Netsilik had had very little contact with the western world. The extensive notes made by Amundsen about their customs, as well as the large collection of Netsilik clothing and equipment he gathered, proved to be one of the biggest tangible results of his expedition.

6. He was the first to reach the South Pole

After the voyages with Gjøa, Amundsen began to plan and raise funds for an expedition to the North Pole. But when both Frederick Cook and Robert Edwin Peary announced in 1909 that they had reached it, Amundsen chose to change his plans.

His next journey would instead go to Antarctica. Amundsen had received Fridtjof Nansen's approval to borrow the polar ship Fram.

Before the expedition left Madeira, Amundsen informed the participants of his changed plans, and sent home letters and telegrams to Captain Robert Falcon Scott, who was in New Zealand on his way to Antarctica.

Read more: Admundsen v Scott: The Deadly Race to the South Pole

After extensive preliminary studies, Amundsen chose a different starting point for the advance towards the South Pole than the previous British expeditions, namely the Bay of Whales, in the middle of the Ross Barrier.

This starting point was closer to the South Pole, but the terrain to the south was completely unknown, so the decision was not without risk.

Amundsen set out with 4 teammates, 52 dogs and 4 sledges on 19 October, 1911. He arrived at his destination not two months later, on 14 December.

There he recorded scientific data before setting out on the return journey on 17 December. The return trip went even faster: the crew reached the Bay of Whales on 25 January 1912.

In the meantime, Scott had reached the South Pole on 17 January, but he and all his men perished on the return journey. The skills Amundsen had received from the Netsilik people on his previous journey proved invaluable to his success.

7. He flew towards the North Pole in a plane…

An expedition in the Northeast Passage that resulted in the ship freezing into place every winter for three consecutive years only increased Amundsen’s interest in polar exploration by aircraft. Two early attempts resulted in failure and the breakdown of the aircrafts.

Amundsen’s dream would be made possible by rich American heir Lincoln Ellsworth. With two Dornier-Wal flying boats, N 24 and N 25, Amundsen and Ellsworth flew north from Ny-Ålesund on Svalbard on 21 May 1925.

They were accompanied by a crew of four: two pilots and two mechanics. After more than 8 hours in the air, the planes landed at a latitude of 87° – around 330 km (200 miles) short of the pole.

There, they discovered that one of the aircraft had been damaged during take-off and would not be able to fly again. Almost three weeks passed, during which the world gave up hope of seeing the expedition's participants again.

Meanwhile, the six men on the ice fought to get up with the one plane. Using hand tools, they succeeded in levelling a primitive runway, and the six men took off on the remaining plane.

With the last drops of fuel, the plane reached the north coast of Nordaustlandet (an island of the Svalbard archipelago), where they were spotted by a passing ship, who brought them back to civilization.

8. …and in an airship

One year after their first flight, Amundsen and Ellsworth set out on a new one, this time in an airship. The airship Norge was built in Italy by engineer Umberto Nobile, a colonel in the Italian air force.

The expedition was organised by the Norwegian Aviation Association, which had also been responsible for the expedition with the two flying boats. Nobile would pilot the airship, with 15 other men on the crew, including Amundsen and Ellsworth.

On the evening of 11 May, 1926, the Norge started its transpolar flight from Svalbard. It reached the North Pole after just 16 hours and landed at Teller in Alaska on 14 May, after a flight of 72 hours.

The voyage went across the unexplored part of the Arctic. Although visibility was poor on the North American side of the Pole south of 85° latitude, Amundsen could determine that there was no large land area there.

The last large blank spot in the maps had been removed. Amundsen had reached his last, big goal.

9. He went on a lecture tour in Japan

In 1927, Roald Amundsen went on a lecture-giving tour of Japan, at the invitation of the newspaper Hōchi Shinbun. He travelled the country for six months, received a hero’s welcome in many places and talked about his adventures.

Mementos of this trip are displayed at his house, Uranienborg, which is now a museum, south of Oslo.

10. He died doing what he loved

After their airship trip together, Roald Amundsen and Umberto Nobile engaged in a very public feud over who should have been credited with leading the expedition.

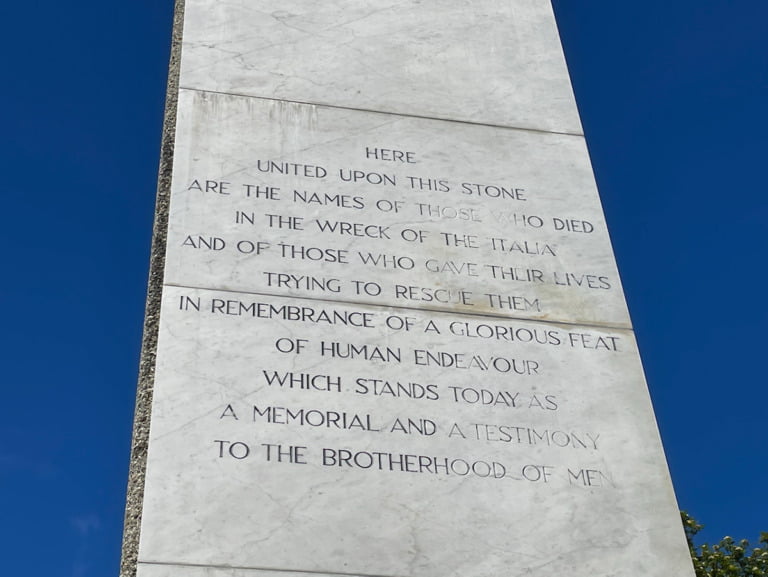

Despite this bitter disagreement, Amundsen felt compelled to organise a rescue expedition to save Nobile when an airship he was leading crashed north of Svalbard in May 1928.

Amundsen boarded a French Latham 47 prototype seaplane in Tromsø to look for Nobile. But tragedy struck and Amundsen and his crew disappeared during the rescue mission.

To this day, what exactly happened to them is uncertain, but the later discovery of debris from the aircraft points to the plane crashing in the Barents Sea, possibly after flying into a dense fog bank. Amundsen’s remains and those of the others on the flight were never found.

Nobile and seven companions were rescued weeks later, but eight of his crew perished.

11. He has a ship named after himself

The MS Roald Amundsen is an expedition ship of the Hurtigruten line, launched in 2019. It can carry 528 passengers, and is the first of the line’s ships to have hybrid propulsion.

The innovative hybrid propulsion system reduces the ship’s fuel consumption and CO2 emissions by 20 per cent.