From the mountain trolls to the mighty ocean-dwelling kraken, Norway is full of fascinating creatures. Learn all about the mythology, and how to protect yourself should you encounter one of them.

So, you're thinking of travelling to Norway? No doubt you've heard all about the famous Norwegian sights: the fjords, the aurora borealis, the bizarre Christmas foods, and you want to experience it all for yourself? We don't blame you!

But perhaps you're unaware of the perils of your travels? Here, we don't mean the natural perils – we're talking about the unnatural ones.

The thing that lurks just beneath the surface of the water. The mountain outside your window that you could've sworn wasn't there yesterday. The strange music that you can't seem to help but follow…

Not to worry! We've compiled this guide to ensure that you can enjoy all Norway has to offer without risking your immortal soul.

As an experienced fairy-tale traveller, we have no doubt that you've wrangled with monsters before. You've probably successfully hidden from the giants of the Cornish coast, out-screamed the banshees in Ireland, and fended off the Beast of Gévaudan with doggie treats.

Therefore, you're probably feeling pretty confident about your chances of surviving whatever horrors are lurking in the Norwegian mountains. All the same, it can never hurt to be too prepared.

Most of the stories in this collection can be found in the University of Oslo's digital collection of fairy-tales and myths. So far the database only exists in Norwegian, but if you want to read the stories for yourself, we have added the catalogue number for each story after the title.

The Norwegian Troll

Where: Mountains, forests and under bridges

Perhaps the most famous fairy-tale creature in Norway is the troll. You can find them everywhere from cute souvenirs in giftshops to big statues in forests. We wouldn't want to insult an experienced fairy-tale traveller such as yourself by going over the basics, but here's a quick refresher just to jog your memory.

The word “troll” is sometimes used in Scandinavian folklore as an umbrella term to describe a whole variety of different creatures. However, in the interest of specificity (and, by extension, your safety), when we refer to trolls in this guide, we consider the three Us: they are ugly, unpleasant and (h)umungous.

Norwegian trolls are often bigger than humans, and some can even be as big as the mountains themselves. You might think their size would make them very hard to miss, but trolls can blend in extremely well with surrounding nature. Furthermore, trolls have an exceptional sense of smell and if they catch your scent, it can be pretty difficult to escape.

Luckily, most trolls hide during the day, as sunlight turns them to stone. Yet, in the daytime it is sometimes possible to find evidence of where the trolls have been. For example, I was hiking in Sangefjell recently with a Norwegian friend who informed me that the reason there are rocks littered everywhere is because trolls on opposite mountains tend to throw them at each other during the night.

How to escape

Trolls may be renowned for their size, but they're also known for their stupidity. If you're caught by a troll, then outwitting it may be your only way of survival. Even animals have been known to outsmart trolls. In “De tre bukkene Bruse” (The Three Billy Goats Gruff) (AT122E), three billy goats want to cross a bridge that has a troll underneath.

The small one goes first, and the troll immediately jumps up and threatens to eat him. The small one says if he waits, another bigger goat will come next and he'll make a much better meal. The troll agrees and the small goat crosses.

The medium-sized goat then steps onto the other bridge and again, the troll jumps up to eat him. However, the medium-sized goat promises the troll the same thing as the small goat, and while the troll is unhappy, he agrees and lets the medium-sized goat pass.

Now it's the big goat's turn. The troll jumps out, but the big goat rams him with his horns and knocks the troll into the river. The troll drowns and the three goats live happily ever after.

However, this strategy has several conditions. First, you need to at least be as smart as a billy goat (we're sure you are, of course, but not everyone is). Second, the troll has to be one of the cleverer ones – that is, one that is capable of human speech. Third, we are unsure whether trolls speak any language other than Norwegian or how strong their dialect is.

In the worst case scenario, your best chance is either to hold out until dawn or find a church and ring the bell, as trolls hate the sound of church bells.

However, as with most things, the best strategy is a preventative one. Do not go out hiking in mountainous areas in the dark. Even if you don't encounter a troll, the wilderness can be an extremely dangerous place and you can easily get into serious trouble.

Nøkken

Where: Lakes and rivers

The nøkk (or nykk) is a water spirit that lives in lakes and rivers. It is a shapeshifter that often takes the form of a white horse or beautiful young man in order to draw unsuspecting victims to a watery grave.

Sometimes it also uses music to lure people to it, which often leads to it being confused with another water spirit, the fossegrim. Young unbaptised children and pregnant women are particularly at risk, but that doesn't necessarily mean it's safe to go for an evening stroll around the lake if you don't fit into these two groups, as the nøkk is particularly dangerous after sundown.

Even catching a glimpse of the nøkk or hearing its cry is risky, as it is often a warning that someone is going to drown.

Sceptics may try and argue that the nøkk is merely a way to keep children from playing near deep water. Arguably, sceptics have kept the nøkk well fed for many years.

While the nøkk could be in any lake, Theodor Kittelsen‘s inspiration for his paintings of the creature was Telemark's Tårntjernet lake, which is the biggest lake in Jomfruland National Park. We therefore ask any aspiring fairy-tale travellers to take particular care when walking in this area.

How to escape

If, despite our warnings, you still find yourself caught by the nøkk, there is one thing you can do.

It may be tempting to take a deep breath before you hit the water, but instead you need to use the last of your air to yell the nøkk's name. In the folktale “Nøkken som hest” (The Nøkk as a Horse) (ml4095) from Hedmark, three boys are playing by a river when a white horse emerges from the water and lies on the bank next to them.

Immediately, the two eldest boys clamber onto its back. Of course, the youngest one wants to join too, so he calls to his brothers:

“Je skulde ha nykke meg oppaa je eu!” (“I want to get up too!”)

Without meaning to, the boy had said the nøkk's name, and upon hearing it, the nøkk immediately canters into the water, taking the two eldest boys with it but allowing the third to escape.

Norway is known for its range of dialects, and we have not confirmed whether the nøkk accepts all pronunciation variations of its name.

We would therefore recommend to non-Norwegian speaking travellers who are interested in visiting the Norwegian lakes to learn how “nøkk” is pronounced in that municipality – or at least have a string of possible pronunciations prepared, just in case.

Fossegrimen

Where: Waterfalls and watermills

Much like the nøkk, the fossegrim is a water spirit and shapeshifter. However, instead of lakes and rivers, the fossegrim tends to live under waterfalls and watermills (“voss” or “foss” means waterfall in Norwegian).

Furthermore, the fossegrim appears to be much less malevolent than the nøkk, as it appears to want an audience to its music rather than want to use its music to drown anyone. Apparently, it is particularly fond of the Hardanger fiddle.

The fossegrim's Swedish counterpart is “Strömkarlen”, whose name translates to “the river guy”.

How to escape

In theory, the fossegrim is not dangerous – unless you're so caught up in listening to the music that you accidentally fall into the waterfall. You may even be able to persuade it to pass on his musical talents.

In the stories of “Fossegrimen Læremeste i Felespill” (The Fossegrim is the Master at Teaching the Fiddle) (ml4090), it teaches a young man how to play the fiddle.

The price is a sacrifice, often a young goat or a sheep, thrown into a waterfall running north on a Thursday evening. The teaching process seems to be quite quick if painful, as the fossegrim takes the hand of the pupil and bends and twists it until it bleeds.

By the end however, you'll be able to play as well as any virtuoso – and without the student debt from training at music schools. However, your new-found gift will often depend on the quality of the payment: animals are without much meat on them or that you've already taken a bit out of will result in only taught to tune the instrument, not play it.

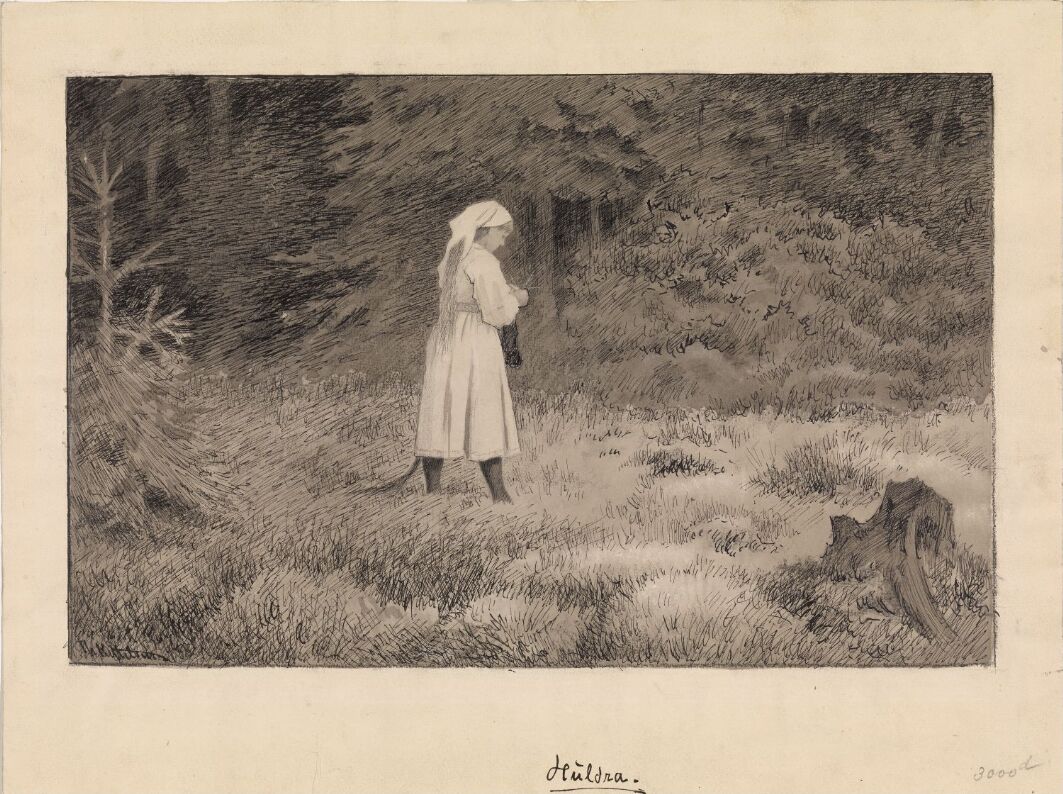

Huldra

Where: Farms and forests

At first glance, the hulder looks like a very beautiful yet ordinary human woman. At second glance, however, you may notice that she has a long, cow tail – which is when you'll realise that she is far from human.

Stories of the hulder are particularly common among dairy farms in the mountains, where they usually wander out of the forest to find a young man to seduce and/or marry. However, there are stories of men trapping an unsuspecting hulder and taking her home to marry (ml5090). In these cases, a hulder will lose her tail as soon as she says her vows and become fully human.

There are also stories of “huldrekall” (male hulder) taking human women, but these are much less common. We do not recommend marrying a hulder during your stay in Norway, purely on the basis of the amount of paperwork that would be involved.

The hulder can also be generous, especially if you do them a favour. In “Jordmorsegna” (Midwife to the Fairies) (ml5070), a huldrekall asks a human woman to act as a midwife for his hulder wife, who is about to give birth. The woman agrees, the hulder baby is born, and the woman is rewarded handsomely.

Their duality is reflected in their musical talents. Like the nøkk, the hulder can use their music as a way to lure people to them. Alternatively, the hulder may teach human people their songs and skills, like the fossegrim.

How to escape

As with many of the creatures listed here, as long as you're respectful to the hulder, you often have no reason to worry. If you are approached by a hulder asking for help, be sure to do your utmost to fulfil their request and you will probably be well compensated for your trouble.

But what if the hulder wants to marry you, and you a) aren't really looking to settle down or b) are otherwise engaged? If this is the case, then “throwing steel” (aka literally throwing a steel knife or shooting a steel bullet) over the hulder will take away their power.

In the story of the “Huldrebryllup på setra” (The Hulder Wedding on the Farm) (ml6005), a young girl is sitting alone when a group of “huldrefolk” (hulder people) suddenly surround her and start preparing her as a bride to an old huldrekall.

She manages to send her dog to alert her boyfriend of the situation, who comes running and “throws steel” over them. The huldrefolk flee and the couple very practically decide that since she's dressed as a bride, they may as well marry.

In short, be nice to the hulder, but always best to have steel on hand. You may also want to make sure that you have a good aim.

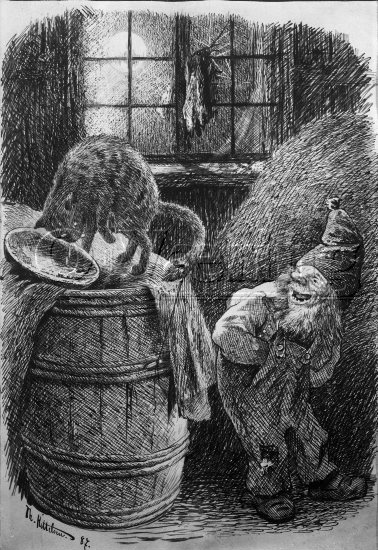

Norwegian nisse

Where: Homes and farms

A nisse is a small creature that is often connected to a specific place such as a farm or a house, but there are stories where the Norwegian nisse becomes attached to people (ml7020).

They are often described as having a similar appearance to a garden gnome – a small old man (or woman) with a red pointy hat – and behave in a similar way to house goblins or brownies. However, most Norwegians never see their nisse and only know they are there due to the signs they leave behind.

.jpg)

If you treat your nisse well, they can be extremely helpful and perform chores for you or look after the farm animals. The nisse also take on the role of Santa Claus in Norwegian households and leave presents for the children of their home.

But if you mistreat your nisse or offend it, then it can (and will) do its utmost to make your life as miserable as possible, from hiding your keys to even potentially killing your pets. As Petter Olsen warned in 1936:

“Nissen bodde mest på hver gård. Det var best å være godvenner med den. Var nissen lei for noe gjorde den mange streker.” (The nisse lived on pretty much every farm. It was best to be good friends with it. If the nisse was upset by something, it would pull many pranks) (Hvaler, Østfold – ml7000).

Moreover, a nisse can be extremely fickle. In one such story “Nye klær” (New Clothes) (ml7015), a man wants to reward a hardworking nisse on his farm by giving him new clothes.

However, once the nisse receives the clothes, he stops working, arguing in some accounts that he doesn't want to dirty his new clothes, and in others that he now looks too good to do such work.

In another version of the story, the man accidentally sets out leather trousers for the nisse instead of cloth ones, and the nisse refuses to do any work because the leather trousers are not warm enough.

How to escape

If you believe that your accommodation in Norway has a nisse, then there's nothing to do other than be respectful and polite.

If you come back from a long walk and find all your clothes neatly folded in your suitcase, remember to say thank you. Similarly, if it's your last night and you can't find your passport, politely ask the nisse to return it. In either situation, leaving it a gift, such as a bar of Kvikk Lunsj, can sweeten the deal.

If your host already has a relationship with the nisse, it's best to follow their advice. However, you may want to avoid being too generous, unless you want to risk the nisse following you home.

Oskoreia

Where: The skies, Christmas

When most people think of Christmas in Norway, no doubt they think of snow and burning log fires, and knitted sweaters and pine trees decorated with candles.

What they probably don't think of is a horde of ghosts racing through the sky, shrieking and wailing, ready to snatch up any unfortunate soul that stumbles into its path. And yet, Christmas is when the Oskoreia rides.

According to the Store norske leksikon, Oskoreia (or the Åsgårdsreie) is made up of “ghosts, brawlers, murderers, drunkards, traitors, loose women, fools and trolls“, who all ride through the air on firey horses. They are lead by Guro Rysserova, also known as “Rumpe-Guro”, sometimes along with her husband, Sigurd.

Not much is known about Rumpe-Guro, but her main characteristic is that she has a horses tail, and in that way is similar to the hulder. She rides a black horse named Skokse or Skerting, while Sigurd's horse is named Grane.

In some stories, they exist to cause a nuisance and will storm through your house, making a considerable mess and eating your Christmas dinner. In other stories, they steal the souls of anyone unfortunate enough to be in their path, thereby dooming them to an eternity of extremely loud debauchery.

How to escape

Oskoreia is a form of the Germanic myth known as The Wild Hunt, and as such, they can be extremely difficult to escape and near impossible to outrun.

Even other magical creatures are not safe from The Wild Hunt, as evidence in the story “Jaget hulder (Den ville jakt)” (Hunted Hulder (The Wild Hunt)) (ml5060), wherein a hulder is pursued and killed by a huntsman from The Wild Hunt.

To reduce your risk of having your Norwegian Christmas ruined by Oskoreia, most advice seems to be to stay inside. If you have to go outside, stick to the paths that you usually tread and avoid crossroads at all costs.

Since folklore suggests that the Oskoreia is made up of sinners, painting a cross on the door of your home can deter them from storming through your home. If you have a nisse in your home that you're on good terms with, they can also protect your home from Oskoreia.

If you are unlucky enough to be in the wrong place at the wrong time, then crossing yourself or lying face down in the shape of a cross might save you… however, we cannot guarantee that this is the case.

Apparently, people who are not ready in time for Christmas are at a greater risk of being taken. Therefore, you might want to start making your Christmas preparations now (if you haven't already) – just to be safe.

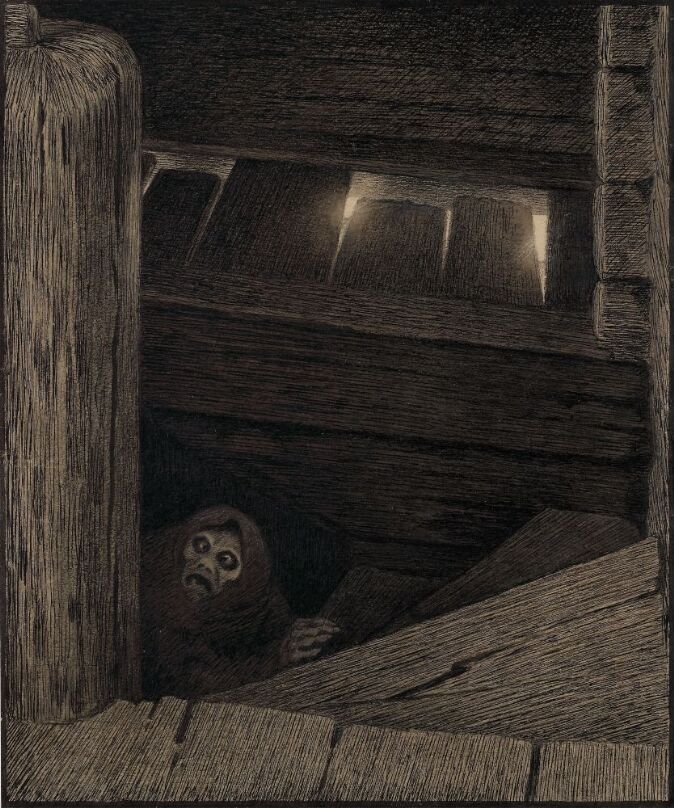

Mara

Where: Your bedroom

In cultures all around the world, there are stories of people waking up being unable to move with a heavy pressure on their chest, as if something is sitting on them. In some cases, something is.

In Scandinavia, the being responsible for this is known as the mare. The mare is a malevolent being, usually characterised as a female, whose name comes from the Norwegian word “mareritt” (nightmare).

She enters places through cracks in the walls and under doors to sit on her victim's chest while they're sleeping and torture them with bad dreams. She can affect both humans and animals, particularly horses.

Waking up paralysed and feeling as if someone is pressing on your chest might also be due to the scary but harmless condition known as sleep paralysis, and it can be difficult to know whether you've experienced something natural or supernatural.

One way to tell is if you wake up with your hair matted together in what is known as “marelokk“. Nisse have also been known to knot people's hair in the sleep as a practical joke. However, if your house does not have a nisse, you may have been visited by the mare.

How to escape

A visit from the mare can definitely be unpleasant and disturbing to live through, but ultimately, it won't do you any harm. However, if you find yourself the frequent victim of the mare then you may need to take appropriate action.

In the story “Gift med mara” (Married to the Mare) (ml4010), a man who is often visited by the mare is advised to block all the cracks and holes in his room, except for one – which he should wait to block until the mare has arrived. He does so and as soon as the mare returns, he blocks the final hole.

Immediately, the nightmarish mare turns into a beautiful woman. The two get married and are extremely happy together… until one day, the man unblocks the holes in the room one day while cleaning, and his wife immediately vanishes. He never sees her again.

As with the hulder, we don't advise you to trap and marry the mare due to potential visa issues. However, if you're frequently having bad dreams, then sealing all the gaps and cracks in your room before you sleep may keep her out.

Although, if you're staying in rented accommodation in Norway, we do not advise doing anything permanent to the room without consulting the owners first).

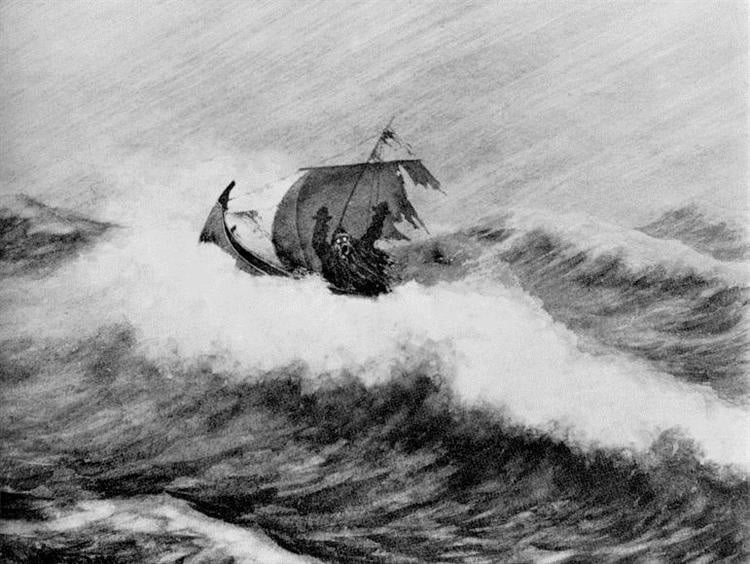

Draugen

Where: North Norway

Not to be confused with the draugr in Iceland, the draug in North Norway or “havdraug” (sea draug) used to be a regular person – until they drowned at sea.

The draug often appears wearing the traditional fishermen's oilskins (known as “skinnhyre” in Norwegian). Luckily, they are easily recognisable due to their lack of head (or a head of seaweed, according to some accounts… which is just as distinctive).

If you're on the water, you can spot an approaching draug by the half boat they'll be sailing in. To give you an idea of what you're looking for, the municipality of Bø has a half boat on its flag as a direct reference to the draug.

However, this is where the good news ends, as while the draug may have been human once, all of its humanity has long been washed away. If you see a draug or hear its scream, then a death will surely follow – and you should just hope it isn't your own.

The north of Norway has a strong fishing tradition. Yet, with high reward comes a high risk as the water around the northern Norwegian coast can be treacherous and feature two of the strongest tidal currents in the world: Saltstraumen near Bodø and Moskstraumen in Lofoten.

Even today, fishing is one of the most dangerous jobs in the world. Sceptics will try and convince you that stories of the draug are just an old way of rationalising the loss of loved ones at sea… but you and I know better.

How to escape

Naturally, one of the easiest ways to avoid the draug would be to steer clear of the northern Norwegian coastline… but then of course, you would also be depriving yourself of some truly amazing sights.

However, if worst comes to the worst and you do encounter a draug, the folktale “Sjødraugane og landdraugane” (The Sea Draug and the Land Draug) (ml4065) may hold the answer.

There are several variations of this story, but they all depict a Norwegian man being pursued by a draug. He manages to escape by running through a graveyard and yelling for the spirits of the Christian men buried there to rise up and save him. The ghosts then overpower the draug and throw them back into the sea.

Unfortunately, we have no other accounts on record of people who have encountered a draug and survived without running through a graveyard. If you do so, please write in and let us know.

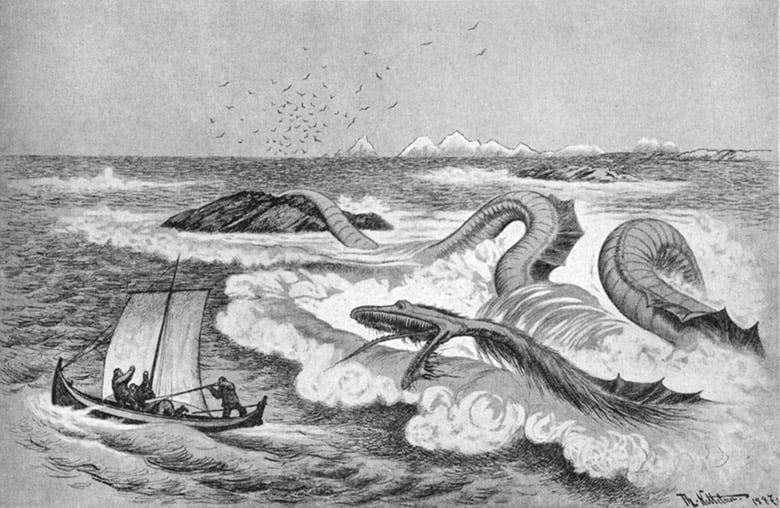

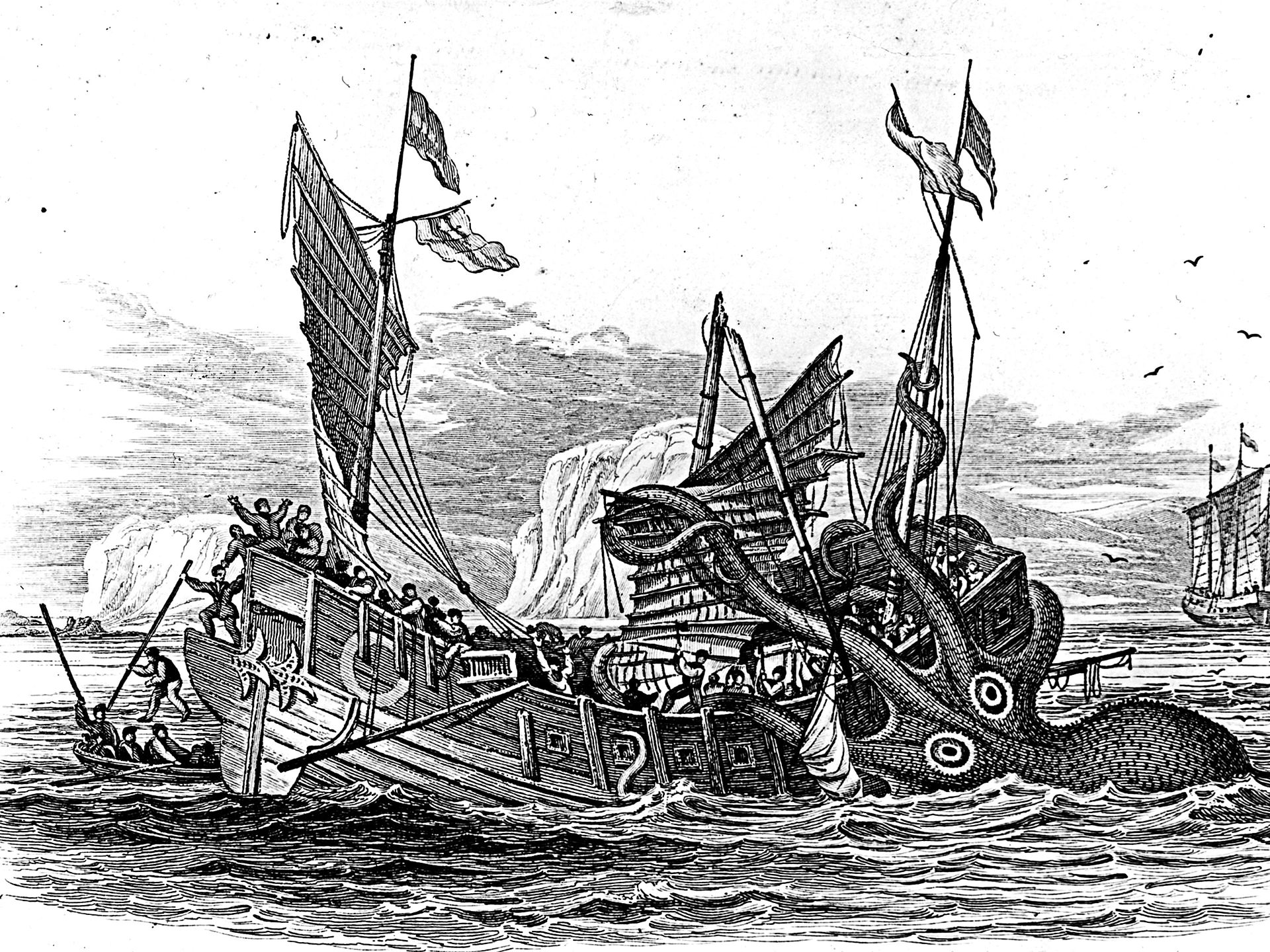

Kraken

Where: The North Sea

If you visit the coast of Norway in the summer when the weather is pleasant and the sea is calm (and there are no draug about), you may be tempted to take a boat trip out to sea.

However, according to Norwegian fishermen, if you row several miles out to sea and find that the water is much shallower than you expect it to be, and there is an abundance of fish to be had, that is how you know that the kraken is beneath you.

While we now think of the kraken as a type of giant squid, Norwegian folklore describes it very differently. The kraken is first accounted for in writing in 1755 by a Danish man named Erik Pontoppiden in his book “The Natural History of Norway”.

According to Pontoppiden, the kraken is so big that it is doubtful whether anyone has seen it in its entirety before. Its back looks like a cluster of small islands, and Pontoppiden attributes Scandinavian fishermen's accounts of floating and disappearing islands to the kraken surfacing for a short while.

The kraken is also said to have horns “which grow thicker and thicker the higher they rise above the surface of the water and sometimes they stand up as high and as large as middle-sized vessels.”

The English translation of Pontoppiden's book is when the word “kraken” entered the English language. However, the legend of the kraken arguably goes as far back as the Icelandic sagas.

Both the Saga of Örvar-Odd and “Konungs skuggsjá” (the King's Mirror) describe a similarly gigantic sea monster known as “hafgufa”. In subsequent English translations, hafgufa is often translated as kraken.

How to escape

Despite its fearsome nature, the kraken does not seem to actively hunt people. According to Pontoppiden, the kraken mainly eats fish and will emit a specific smell in order to draw the fish to it. Once it has finished eating, the surface of the water becomes covered with a thick, muddy slime as the kraken digests its fishy meal.

A similar process is described in the King's Mirror, where the author says that when the hafgufa is hungry, it belches loudly to draw fish to it before opening its mouth and waiting. All the fish crowd inside looking for food – only to become food themselves once the hafgufa closes its jaws.

However, while fishermen are often happy to find the kraken due to the amount of fish that comes with it, they have to keep an eye on the depth. If they find the water is getting shallower, they need to get out the way quickly as it means that the kraken is surfacing, and its horns and the associated waves could wreck the boat.

Similarly, when the kraken sinks, it creates a whirlpool strong enough to easily drag fishing boats down to the depths with it.

Therefore, if you do decide to take a trip on the North Sea, we recommend making sure that your boat is equipped with a bathometer and a working engine… just in case.

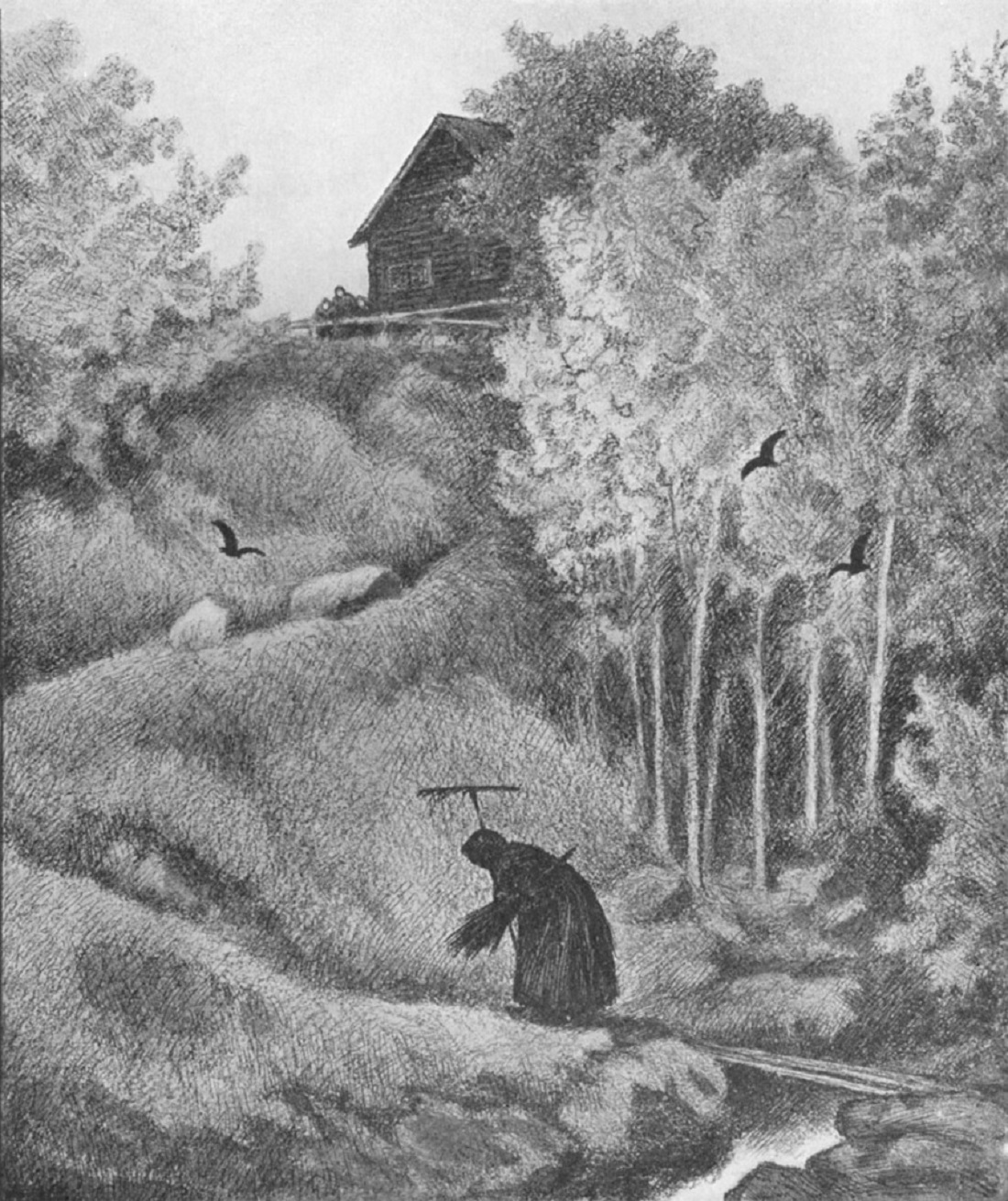

Pesta

Where: Everywhere but mainly western Norway

Given the current global situation, it may be easier than thought to imagine the fear that gripped Norway when “Svartedauden” (the Black Death, aka the bubonic plague) finally arrived by ship in Bergen in 1349.

This signalled the first outbreak of the plague in Norway, which then continued to die down and reappear in waves until 1654. While the plague affected the whole country, it was best documented in Western Norway – possibly due to its arrival in Bergen.

At the time, the plague is estimated to have killed a third of the global population, and Norway's own population was significantly impacted. It's hardly a wonder that the plague soon manifested in people's consciousness as its own character.

Pesta (from the Norwegian word “pest”, meaning plague) is described as a wizened old women with black eyes who travelled from town to town carrying both a rake and a broomstick.

If you saw her scraping the soil with a rake, you could take comfort in the fact that some people in your village would survive the plague. If you saw her sweeping with her broom, it was already too late for you.

How to escape

Unlike the rest of the creatures mentioned in this article, Pesta is merely an omen of what is to come and not what you need to protect yourself from. In the folktale “Pesta og fergemannen” (Pesta and the boatman) (ml7085), Pesta asks a boatman to transport her across the water. Not realising who she is, he agrees.

Halfway across the water, he figures it out and is immediately terrified. He tries to make a deal with her, that she can spare his life as payment for the ferry ride. Pesta agrees as long as his name is not in her book.

Unfortunately for the ferryman, his name is indeed there – but Pesta agrees to make it a quick, easy death.

Fortunately, due to modern medicine, the bubonic plague is no longer the threat it once was, and you certainly do not need to worry about meeting Pesta in Norway.

However, if you want to avoid one of her descendants, Korona, then the best thing to do is to wear a face mask on public transport and wash your hands.

Have you encountered any fairytale creatures in Norway? Let us know in the comments, so that other travellers might be better prepared for their trip to the Wild North.

This may be my favorite post. I’m still working through all of the links you provided. Thank you so much.

Thank you so much for your lovely comment! I’m really glad you enjoyed it! 🙂

This was brilliant. enlightening, informative and also humorous. Well illustrated too. Thanks!