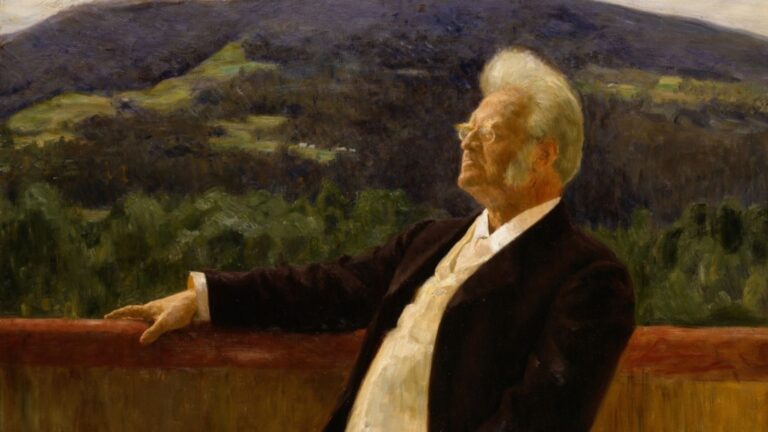

Before Norway had its independence or its own national anthem, it had Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson: a master storyteller with a talent for capturing the heart of a young, growing nation.

From romantic peasant tales to controversial plays criticising social double standards, Bjørnson’s writing didn’t just follow the times, it helped shape them.

But how did a pastor’s son from rural Norway end up writing the national anthem and winning the Nobel Prize in Literature? Let’s dive into the life and legacy of the man known as Norway’s poet chieftain.

A Pastoral Upbringing

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson was born on 8 December, 1832, in Kvikne, south of Trondheim. When Bjørnstjerne was five, his father, who was a pastor, was assigned to a new parish in the Romsdal valley.

This scenic, larger-than-life area would later provide the setting for many of his rural novels. The knowledge he would accumulate about rural life during his upbringing would serve as a basis for the famous peasant tales he would later write.

Sagas and Peasant Tales

During the first part of his literary career, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson produced a series of rural stories and historical plays. The rural stories told a romanticised version of farm life in 19th century Norway, while the historical plays were heavily based on the viking sagas.

This approach allowed him to connect Norway's past with its present, and to strengthen Norwegian cultural identity.

Works like the peasant tale “Synnøve Solbakken” (1857), also translated as “Trust and Trial” or “Love and Life in Norway”, propelled him to the forefront of Norwegian literature.

Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson and the Transition from Romanticism to Realism

It’s impossible to talk about literature (or art) in 1800s Scandinavia without mentioning romanticism and realism (keep reading if you’ve never heard of those). At the beginning of the century, Norway was re-establishing itself as a separate nation.

After years of being ruled by Denmark, it gained its own constitution and some degree of independence, even though it was technically in a union with Sweden.

Still, Norway felt like a young nation trying to find its identity. Writers wanted to celebrate Norwegian history, nature, and the spirit of the people – the perfect moment for Romanticism.

Romanticism

Imagine that you’re watching a movie showcasing life on a small Norwegian farm by a fjord. If the movie would follow the romanticism style, it would be filled with dramatic music, sweeping mountain views, and noble characters who speak in a poetic language.

Villagers are brave and their lives are filled with tragedy and emotion. Even when things are sad, they’re beautifully sad.

Romantic novels were focused on emotion, imagination, and the individual. They often looked back to history and myths, and their objective was to stir the reader’s heart and soul.

Realism

Now imagine you’re watching a different movie, still about the same topic, but following the realism style. This movie takes place in the same village, but the struggles feel very real.

A farmer worries about his harvest following a rainy summer. A young couple struggles to make ends meet.

Characters don’t speak in long, poetic dialogue but in everyday language. There is beauty here too, but everything feels more raw, more real, and the beauty is grounded in real life.

Realistic novels focused on everyday life, real people, and believable situations. They showed the world as it really was, and the objective was to make readers think and understand society, and sometimes even to provoke change.

Henrik Wergeland (1808–1845) was one of the most important romantic writers in Norway. He saw literature as a way to build a strong Norwegian identity, and Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson saw himself as his heir.

But what Bjørnson did, after years of writing peasant tales and historical plays, was to pivot to realism. Instead of romanticising the past or contemporary farm life, these works exposed real – and sometimes very controversial – social issues.

One of these works, En hanske (1883, A Gauntlet), attacked the double standard of sexual morality. In this play, Bjørnson condemned the hypocrisy that demanded sexual purity of women, but not of men. This aligned him with early feminist ideas.

The play was ahead of its time and provoked debate across all of Scandinavia. In another example, Redaktøren (1875, The Editor) Bjørnsom takes aim at corruption in the press and local politics, exposing how newspapers could be used as tools of personal gain and manipulation.

This was a direct commentary on the influence of the media and how editors could influence public opinion or protect their own interests instead of serving the common good.

Plays like this positioned him firmly within the broader movement of socially engaged drama, alongside other playwrights of the time – most notably Henrik Ibsen, author of A Doll’s House (1879).

Champion of the Norwegian Language

It seems strange to think about it today, but the language of choice for everything culture in Oslo in the early 19th century was Danish, not Norwegian. Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson was a passionate advocate for changing that.

As a theater critic, he insisted that Norwegian audiences should hear their own language on stage rather than imported Danish, and even staged a noisy protest against the hiring of Danish actors.

He respected Ivar Aasen’s work in building Landsmål (now Nynorsk) from rural dialects, but believed that the national language should instead evolve from the written Danish traditionally used by the educated classes.

The version of Norwegian that is by far the most used today, Bokmål, largely follows the principles Bjørnson championed, demonstrating that he left a lasting imprint on Norwegian identity that goes beyond literature.

Norway’s National Anthem

In the early 1860s, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson wrote the lyrics to Ja, vi elsker dette landet (“Yes, We Love This Country”). The poem was first publicly performed in 1864 during the 50th anniversary of Norway’s constitution, set to music composed by his cousin, Rikard Nordraak.

At the time, Norway was still in a union with Sweden, and the song’s heartfelt celebration of the Norwegian people, landscape, and history struck a chord. The tone of the poem was patriotic but not aggressive, which helped it gain broad support even during politically sensitive times.

Over the following decades, Ja, vi elsker gradually became the de facto national anthem, widely sung at public events, school ceremonies, and national holidays.

Surprisingly, it was only officially adopted by parliament as the national anthem in 2019, a largely ceremonial move that essentially confirmed what was already there.

Nobel Prize in Literature

In 1903, Bjørnstjerne Bjørnson became the first Norwegian to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature.

The Nobel Committee awarded him the prize “as a tribute to his noble, magnificent, and versatile poetry, which has always been distinguished by both the freshness of its inspiration and the rare purity of its spirit.”

The award acknowledged not just his poetic and dramatic works, but also his long-standing influence on the cultural and moral life of Norway. Although Bjørnson had not published major new literary work in the years immediately leading up to the award, the committee recognised the full scope of his career.

At home, receiving this honour solidified Bjørnson’s reputation as dikterhøvdingen — the poet chieftain. On the international stage, it elevated Norwegian literature and gave it a new audience.

It was a moment of national pride during a period of growing Norwegian cultural confidence, just two years before the dissolution of the union with Sweden in 1905.