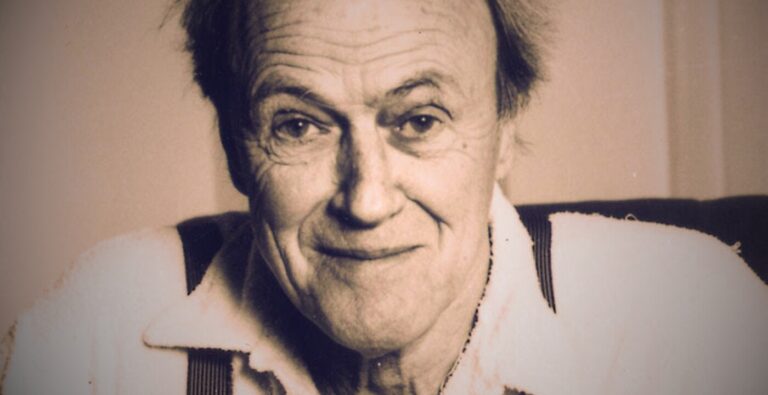

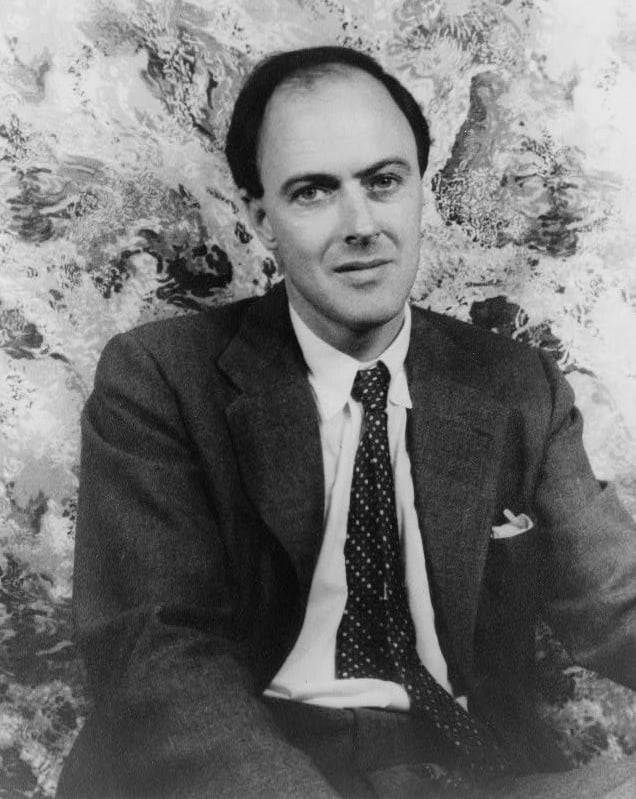

Few authors have shaped the imagination of children and adults quite like Roald Dahl. Although he is usually described as a British writer, Dahl’s upbringing, family history and cultural identity were deeply entwined with Norway.

He grew up bilingual, spent childhood summers in Tjøme and Hardangervidda, and filled his later writing with Scandinavian humour, landscape, folklore and sensibility.

Dahl’s life was far more complicated, darker and more surprising than many readers realise.

Beneath the playful fantasy of Matilda, The BFG and Charlie and the Chocolate Factory was a man shaped by grief, war, loss and an outsider’s perspective on the complexities of belonging.

This is the story of Roald Dahl through ten revealing facts, each shedding light on the Norwegian roots, paradoxes and creative forces that shaped one of the most influential writers of the 20th century.

1. He Was Born Into a Norwegian Immigrant Family in Wales, And Grew Up Fluent in Norwegian

Roald Dahl was born in Llandaff, near Cardiff, in 1916 to Norwegian parents who had migrated to Wales during the great boom of the coal and shipping industries.

His father, Harald Dahl, had moved from Paris in the 1890s to establish a shipbroking business in one of the world’s busiest coal ports.

Although Dahl spent his childhood in Britain, the Dahl household was unmistakably Norwegian. The family spoke Norwegian at home, celebrated Norwegian traditions and travelled to Norway every summer.

Dahl later wrote that he considered Norwegian his “first language,” and that the cadences and humour he absorbed from his mother shaped the “musicality” of his storytelling voice.

His mother, Sofie Magdalene, would read him Norwegian folktales that left an imprint on stories like The Witches and The Twits, where trolls, hags and grotesque creatures emerge from the shadows of Scandinavian folklore.

Norway wasn’t merely part of Dahl’s heritage. It was a core part of his inner imaginative world.

2. His Childhood Summers in Norway Were the Happiest Days of His Life

Every year, Dahl’s mother gathered the children and boarded a series of ships for a long journey home to Norway. Their destination was the family’s holiday paradise in Tjøme, Vestfold, or occasionally the majestic landscapes of Hardangervidda.

For Dahl, these summers became the emotional blueprint for happiness, adventure and freedom.

He later wrote about the long days spent fishing, exploring islands, climbing rocks and listening to his mother’s stories. That sense of wonder, tinged with danger and mischief, is a thread that runs through nearly all of his children’s books.

His autobiographical book Boy includes vivid chapters about these summer adventures. While the British episodes in Boyoften centre on fear, school discipline and cruelty, the Norwegian chapters glow with warmth, safety and joy.

Norway was not just a holiday destination to Dahl. It was home.

3. Dahl’s Life Was Marked Early by Tragedy, And Norway Shaped How He Understood Loss

Roald Dahl’s early life was deeply marked by grief. When Dahl was just three, his older sister Astri died from appendicitis. A few weeks later, his father Harald died of pneumonia, reportedly heartbroken by Astri’s death.

After becoming a young widow, Dahl’s mother Sofie faced a difficult decision: return to Norway to be near her family, or stay in Wales to honour Harald’s dream that their children should receive a British education.

She stayed.

Dahl later described this as the single most important act of love in his childhood. Sofie became the emotional centre of the family, and her fierce storytelling, stoicism and Norwegian practicality shaped Dahl’s worldview.

Many of the strong, kind and wise female characters in his books—such as Miss Honey or the grandmother in The Witches—echo Sofie’s influence.

Dahl’s complicated, lifelong relationship with themes of death, danger and dark humour can be traced back to these early experiences, filtered through the Norwegian folktales his mother used to comfort and entertain him.

4. His School Days in Britain Were Miserable, And Inspired His Darkest, Funniest Tales

Dahl’s schooling years in England and Wales were famously painful. He despised the rigid discipline, the canings, the bullying and the oppressive structures of early-20th-century boarding schools.

Much of this appears in Boy, but the echoes reverberate throughout his fiction:

- Cruel headmasters become Miss Trunchbull in Matilda.

- Grim boarding school dining rooms become the grotesque feasting scenes in The Twits.

- The strict, cold adults who surround children become the antagonists of almost every Dahl story.

What Dahl added, though, was fantasy-fuelled revenge. His young heroes outsmart, overpower or escape the adults who confine them.

This subversive spirit of children triumphing over cruelty became a signature of his work.

While rooted partly in his British school experiences, its tone owes much to the rebellious humour of Norwegian folklore, where trolls are tricked, witches defeated, and children or farm boys often outwit adults and authority figures.

5. Dahl Served as a Fighter Pilot in the Second World War, and His Wartime Experiences Changed Him Forever

In 1939 Dahl enlisted in the Royal Air Force, becoming a fighter pilot in the Middle East and North Africa. He crashed in the desert, suffered severe head injuries and spent months recovering.

The war continued to shape his life. Dahl later served as an intelligence officer in Washington, D.C., where he moved among diplomats, spies and politicians. These experiences sharpened his observational skills, his distrust of authority and his fascination with the absurdity of human behaviour.

His early short story collections, such as Over to You (1946), draw directly from his time in the RAF. Even in his children’s books, the shadows of war linger: missiles, explosions, totalitarian villains, or chaotic, dangerous worlds that must be navigated by brave young protagonists.

Dahl once said the war “turned me cold,” replacing the boy who longed for home with a more hardened, sceptical personality. This tension of innocence versus danger is at the heart of his writing.

6. Dahl’s Writing Hut in Buckinghamshire Was Inspired by Norwegian Cabins

Dahl famously wrote in a small, isolated hut at the bottom of his garden in Great Missenden, Buckinghamshire. He worked at a wooden table with a yellow legal pad, sitting in an old armchair, surrounded by quirky personal artefacts.

What many readers don’t know is that this creative refuge was inspired by traditional Norwegian cabins, or hytter.

Dahl adored the simplicity, isolation and practicality of the traditional Norwegian cabin. His writing hut became his English version of a hytte, a place where he could shut out the world and inhabit his imagination fully.

Inside the hut he reproduced a sense of Nordic ritual:

- a strict method of arranging his writing tools

- a dust-free, distraction-free environment

- a rhythm that resembled the stillness of time spent in the Norwegian countryside

He wrote nearly every major children’s book there, from Danny, the Champion of the World to The BFG and The Witches.

7. Norway Appears Throughout His Fiction, Often in Disguised or Surprising Ways

Although Dahl rarely set his stories explicitly in Norway, the country’s presence lingers in ways big and small:

The Witches: The unnamed grandmother is unmistakably Norwegian, with Norwegian folktales, habits, diction and worldview. The book’s witches behave like Scandinavian troll-women, and the dark forests and stormy coasts recall Norway’s landscapes.

The BFG: The Giant’s playful, mishmashed language echoes the English spoken by Norwegians. It's a hybrid tongue Dahl heard throughout his childhood. The BFG’s outsider status mirrors Dahl’s own cultural fluidity.

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory: Scholars have traced descriptions of Willy Wonka’s glass elevator back to a story Dahl heard from a Welsh miner in his childhood, a man who described descending into a Rhondda coal mine in terms strikingly similar to Wonka’s descent. The imagery is filtered through Dahl’s Welsh upbringing and Norwegian sense of allegory.

Matilda: The countryside scenes of Miss Honey’s cottage echo the pastoral landscapes of Tjøme and Radyr, filtered through Dahl’s nostalgia.

Danny, the Champion of the World: Dahl considered this his most personal book. The gentle father-son relationship and forest settings reflect both Norwegian storytelling and the rural idyll Dahl associated with his early childhood home in Radyr.

Norway was rarely foregrounded but was always present. It was a quiet, steady heartbeat beneath Dahl’s worlds.

8. Dahl’s Life and Legacy Are Not Without Controversy

In recent years, Dahl’s legacy has been scrutinised for several reasons, including antisemitic comments he made in interviews later in life. These remarks have been widely condemned by his family and by organisations connected to his estate.

There have also been debates about the darker, crueler aspects of his stories. Yet many scholars argue that Dahl used darkness not to harm children but to validate their experiences. Children recognise cruelty, fear and injustice. Dahl simply refused to pretend the world was gentler than it is.

His stories are ultimately about resilience and empowerment, teaching children that courage and cleverness can overcome unfairness.

Still, the controversies form an undeniable part of his biography, and modern readers often encounter Dahl with a mixture of admiration and critical reflection. His genius coexists with deep flaws — something his own writing seems to anticipate, with its fascination for moral complexity.

9. Dahl’s Relationship With Norway Continued Throughout His Life

Dahl made repeated return trips to Norway as an adult, sometimes to write, sometimes to reconnect with family. He continued to speak Norwegian — albeit imperfectly — and maintained a network of cousins and relatives.

Norwegian newspapers marked his achievements, and his Norwegian identity was cherished within the family. The country shaped not only his childhood but his spiritual sensibility.

His ashes are buried in the churchyard of St. Peter and St. Paul in Great Missenden, but Norwegian flags often appear at his grave, left by visiting fans who recognise the role Norway played in shaping him.

In Norway, Dahl remains widely read and beloved. His books are staples of Norwegian schools and libraries, and Norwegian editions retain some of the linguistic quirks that connect back to his bilingual upbringing.

10. Dahl’s Influence on Global Storytelling Is Immense, And His Norwegian Roots Help Explain Why

Few writers have produced stories that feel so universal yet so personal. Dahl’s work resonates because he was an outsider:

- A Norwegian in Britain

- A Welsh-raised child in English schools

- A wounded pilot navigating the intricacies of power

- A rural maverick in a London-dominated literary world

- A bilingual storyteller translating worlds across borders

This outsider’s gaze is what gives Dahl’s stories their sharpness, mischief and moral clarity. His heroes succeed not because they are powerful, but because they understand how to sidestep cruelty, injustice and absurdity.

Norway’s cultural heritage, folklore, language, humour, landscape, is all woven into that sensibility.

The moral universe of Dahl is closer to Asbjørnsen and Moe than to Enid Blyton. It is a world where danger lurks, magic is unpredictable, and children’s bravery is the most powerful force of all.

I don’t think most Norwegians recognise him as Norwegian, he’s easily the best selling Norwegian authour in history, it took Norwegian years to put him on the tail of an aircraft.