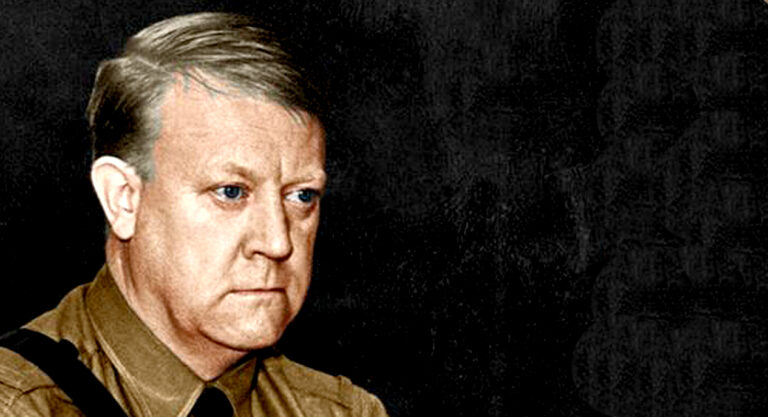

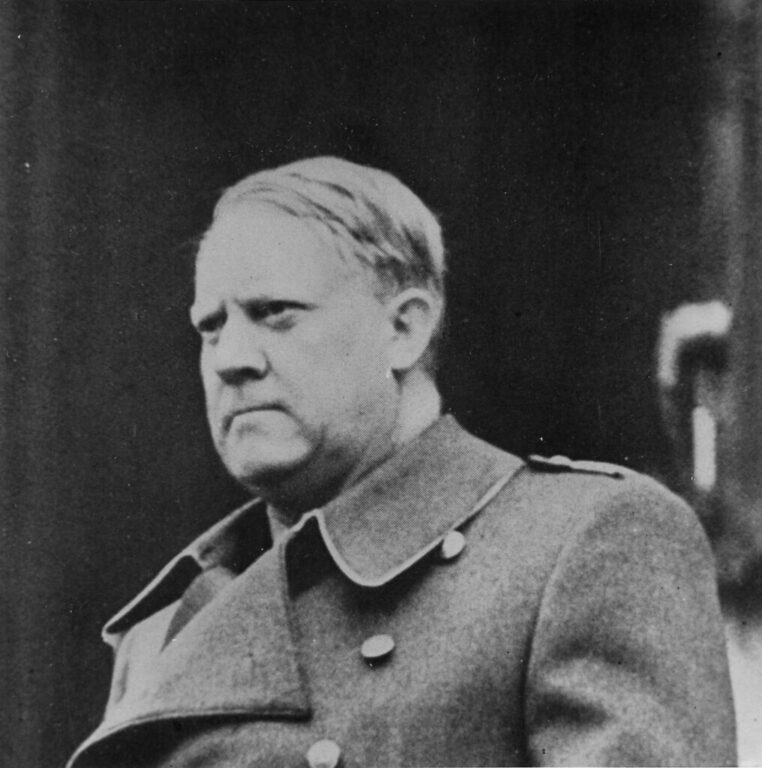

Discover the story of Vidkun Quisling, the infamous Norwegian military officer, politician and Nazi collaborator whose name is known throughout Norway and beyond.

We often hear that the name of a particular celebrity or historical figure is “synonymous with…” something or another. In the case of Vidkun Quisling, it is quite literally true that his name is synonymous with traitor.

But what do we know of the life of this notorious scoundrel who headed Nazi Germany’s puppet government during the occupation? How did he come to betray his country in this way and what were the consequences of his actions?

We’ll do our best to answer these questions in this article, giving you a picture of the man, his story and his crimes – and how his very name would end up being a slur.

Vidkun Quisling’s early years

Vidkun Quisling was born in Fyresdal, in Telemark. His father was a Lutheran pastor who married one of his pupils who was 16 years his junior.

His father’s job as a pastor brought the family to Drammen, southwest of Oslo, where Vidkun Quisling started school. There, he was bullied by some of his classmates because of his Telemark dialect.

Read more: A Timeline of Norwegian History

He was a good pupil regardless, and liked history and natural sciences. He enrolled in the Norwegian Military Academy, and then in the Norwegian Military College, where he graduated with an exceptionally high score for which he was rewarded with an audience with the king.

Quisling’s military career

After a few years working his way up the ranks in the Norwegian military, the traditional military career path dictated that he should specialise himself in a particular country. He chose China, initially, but an ongoing revolution in that country at the time prevented him from going there to work.

Instead, he shifted his focus to Russia. When the country was rattled by the Bolshevik revolution in 1917, Quisling had studied Russia for five years already.

He started as a military attaché in Petrograd in May 1918, arriving in the midst of the turmoil caused by the aftermath of the revolution. His stay in the country was short, but his reports back to Oslo were valuable given the ever-changing situation in Moscow.

The situation quickly became so unstable that he was called back to Oslo in December. He wanted to continue working abroad though, and quickly secured a position as intelligence officer in Helsinki, Finland, which he began in the second half of 1919.

The Ukraine famine

Upon recommendation from his superior in Helsinki, Quisling went to work with Norwegian polar explorer Fridtjof Nansen, who had by then turned his attention to humanitarian work. In that context, Quisling went to Ukraine, where a gigantic humanitarian catastrophe was unfolding.

The country was gripped by a terrible famine, which is now widely believed to have been politically engineered by the Soviet government of Joseph Stalin. Some historians contend that Stalin’s objective with the famine was to quell a budding Ukrainian independence movement.

When it started, the humanitarian disaster was little known outside the Soviet Union. Quisling reported back to Norway about the conditions in the Ukrainian countryside.

In some villages, the entire population was dying of famine. Nansen and Quisling helped make the rest of Europe aware of the situation in Ukraine.

With the help of private donors, Nansenhjelpen (Nansen’s aid organisation) saved thousands of Ukrainians from the famine. Because of this, Nansen and Quisling were very popular with Ukrainians – Ukrainians living in other European countries were particularly grateful that they spread awareness about the catastrophe.

After that, Quisling spent several years as a Norwegian diplomat in the Soviet Union. He also managed British diplomatic affairs there for a period of a couple of years during which Britain and the Soviet Union had no formal diplomatic relations.

Political debut and radicalisation

It is remarkable that Quisling, now known to be a notorious nazi, initially had sympathies for the Soviets. He was even drawn to the communist Norwegian labour movement in the mid-1920s.

While his interest in communism proved not to last, his actions at the time show that he was already then prone to radical political ideas. One of the policies he fruitlessly advocated was the creation of a people's militia to protect the country against reactionary attacks – in other words: a revolutionary militia.

It is unclear what got Quisling to move from communism to fascism, but we can make a few educated guesses. We already know that he was in favour of radical political changes.

We also know that the Soviet government rebuffed him on a few occasions, obstructing some of his efforts to help with the Ukrainian famine and some of his other diplomatic efforts related to Armenia. Quisling took these rejections personally.

The Soviets also accused him of using diplomatic channels to smuggle millions of rubles out of the country. The charge was never substantiated but it is likely that the accusations led him to distance himself from Moscow.

Return to Norway

Quisling returned to Norway in 1929 and served as Minister of Defence from 1931 to 1933, as a member of the Farmers’ Party. By then, he had turned resolutely anti-communist.

He left the Farmer’s Party in 1933 and founded the fascist Nasjonal Samling (National Union). The party promoted nationalist and anti-semitic views.

His ideas caused fear and controversy in the general public, and it seems that Quisling was not very good at reading the political currents.

Despite his party failing to secure a single seat in the Norwegian parliament in 1933, Quisling presented a sweeping constitutional reform bill to make Norway fascist.

The bill was rejected outright by parliament, and his party went into decline when he was quoted by the press telling opponents that “heads would roll” when he achieved power.

The nazi occupation of Norway

Another example of Quisling’s apparent failure to read political currents was his attempted coup coinciding with the invasion of Norway by nazi Germany in the early days of World War II.

On 9 April 1940, the day of the invasion, Quisling gained access to a radio broadcasting studio and declared himself prime minister on the airwaves. He ordered Norway’s military mobilisation to stop. This was part of the nazi command’s attempt to secure a rapid transition of power.

But several things came in the way of that plan. First, the Blücher, a German cruiser which carried most of the personnel intended to take over Norway's administration, was sunk by cannon fire and torpedoes from Oscarsborg Fortress in the Oslofjord.

Then, both the government and King Haakon VII refused to surrender. The king went as far as to say he’d sooner abdicate than appoint any government headed by Quisling.

Quisling’s radio stunt ironically spurred the resistance movement into action. His lack of traction with the Norwegian public led the nazis to abandon him and set up their own puppet government for Norway.

Hitler did write to him to thank him for his efforts, and to promise him some sort of position in the new government, but Quisling was a liability to the nazis at this point, seen simultaneously as a traitor by those opposing the invasion and as a failure by those welcoming it.

Quisling heads the nazi government

Hitler did eventually make good on his promise, and Quisling was appointed Minister-President of the new government of Norway in 1942. His party, Nasjonal Samling, became the only party legally allowed in the country.

Very quickly, Quisling repeated his failure to read the prevailing political currents. In the summer of 1942, he attempted to force Norwegian children to join the Nasjonal Samlings Ungdomsfylking, an organisation modelled on the Hitler Youth.

This backfired spectacularly, prompting a mass resignation of teachers and churchmen, along with large-scale civil unrest. His indictment of a bishop proved equally unpopular, even among his allies.

In response, he only hardened, telling Norwegians that they would have the new regime forced upon them “whether they like it or not.” Berlin soon noted that resistance to Quisling was intensifying as a result, and began to take less and less notice of the man’s wishes.

Quisling participated eagerly in the deportation of Jews for their extermination and sought to win back Hitler’s respect by recruiting Norwegian soldiers to fight for Germany.

At the same time, he was critical of Germany’s silence about its plans for post-war Europe, particularly regarding the status Norway would have in a German-led world.

As the war came to a close, he tried in vain to secure a separate peace deal with the nazis. His failure to negotiate this deal convinced him that his reputation as a traitor was now sealed.

Privately, he had now long admitted that national socialism was defeated. He did his best to antagonise the Allies as little as possible during the liberation of Norway. He ordered the police to offer no resistance to Allied forces, but it was far too little, far too late.

Trial and execution

On 9 May 1945, the day after Victory Day in Europe, Quisling and his ministers turned themselves in to the police. He was indicted during the summer for various crimes including conspiring with Hitler for the invasion and occupation of Norway.

The trial took place in Oslo, in the early autumn of 1945. It was widely publicised and attracted a great deal of attention from the public and the media.

During the trial, Quisling was represented by a team of defence lawyers, but he did not deny the charges against him. He argued that he had acted in the best interests of Norway and that he had not intended to betray his country.

The verdict came down on 10 September. Quisling was found guilty on all counts except a handful of minor accusations.

He was sentenced to death and executed at Akershus Fortress in Oslo on 24 October 1945. In a book written two decades later, Norwegian psychiatry professor Gabriel Langfeldt would say about Quisling's goals:

“They fitted the classic description of the paranoid megalomaniac more exactly than any other case I have ever encountered”.

The legacy of ‘Quisling'

Quisling is now synonymous with traitor in several languages. The term was coined by The Times of London in April 1940, in an article, titled “Quislings everywhere.”

Quisling's legacy in Norwegian history is one of infamy. His actions had a lasting impact on the country and its resistance to the war, and he is often cited as a cautionary tale about the dangers of political extremism and collaboration with oppressive regimes.

A very interesting read. I lived on Nesoya in the late 50’s as a teenager and was introduced from a neighbor to a partial history of her father’s involvement with Quisling. At the time, being a teenager, I didn’t understand the full impact. Such a sad time.

And now under the thumb of Washington, taking part in nefarious activities, such as blowing up undersea pipelines. Germany will not forget!

Several thousand Norwegian men fought on the Russian Front in various Norwegian SS units on the Axis side in WWII; some four hundred Norwegian women enlisted in a nursing corps as well.

We who live in geographically isolated countries with strong armed forces such as the UK and USA don’t appreciate that those who live in central European countries have often had to make a choice between siding with one dominant empire or totalitarian regime or another: there’s no ‘Third Way’ in many cases.

The prime example of this is, of course, Finland – the only liberal democracy to fight on the Axis side in order to regain land under Soviet Russian occupation. Another factor in Finland’s choice is that a lot of her food came from Nazi-occupied Europe after 1940: much of the land taken by the Russians was used for agriculture.

One has to imagine the outlook of a young Norwegian after the defeat of the Allies in Norway in 1940, and their abandonment of that country: the Allies could have held North Norway and dominated the Norwegian Sea and later sea routes to Russia after their victory in the recapture of Narvik from General Dietl’s forces. It was the first successful allied seaborne operation to recapture occupied territory in WWII, driving the Germans up to the Swedish border.

Instead they withdrew in haste to redeploy to France to counter the German invasion which ended the ‘Phoney War.’ The Norwegian Royal Family also fled the country, which wouldn’t ease the feeling of abandonment some Norwegians might have felt – by contrast, the Danish King remained in place, but then he didn’t get time to make a choice in the matter.

At least Quisling did become the unelected head of state – someone to rally to or oppose, which might just be better than someone appointed by the Nazis….

When one looks into the personal stories of the Norwegians who supported the Quisling regime, and were willing to endure the harsh conditions of the Eastern Front and risk to their lives, one does understand the motivation a little better: Norwegian SS soldiers enlisted to fight only the Red Army and not the Western Allies, and generally signed up for six months of frontline service at a time – some of the officers had fought with the Finns in the 1939-40 Winter War, so they at least would have known what they were getting into. The Finns were supported in that war by the Norwegians, Swedes, British and French, amongst others, in their fight against the Soviet Union, which had allied themselves with Nazi Germany in order to occupy a third of Poland and the Baltic States for themselves.

One SS volunteer who also saw the Soviet Union as a greater threat to Norway than Nazi Germany was Per Nesbø, the father of the novelist Jo Nesbø, who joined a unit formed largely from Norwegian police officers, and served on the front besieging Leningrad. Jø Nesbo’s novel featuring Harry Hole ‘The Redbreast’ has several scenes set in WWII based upon his father’s experiences.

Another outcome of the occupation was the inevitable relationships formed between Norwegian women and German soldiers – Anna-Frid Lyngstad, the world famous ABBA vocalist, had a German father. He was repatriated to West Germany and disappeared; her mother, facing persecution in her home country as a ‘Tyskejente’ emigrated to Sweden when Anna-Frid was very young… for which we can all be thankful she learnt to sing there. I don’t think one can read anything new into their song lyrics because of this fact: I believe Benny & Björn wrote them all. In 1978, the West German pop music magazine Bravo tracked down her father in Germany and arranged a reunion in Sweden for them both… a real ‘fly on the wall’ occasion there!

Last time I was in Norway, Vi Menn magazine published an article about the accomplished pre-war Norwegian athlete Charles Hoff, who joined the Hird organisation – a high jumper who “Landet på feil side,” as the title of the article read. That magazine has published other articles about Norwegian collaborators in WWII, a side of the occupation story which has only started to be told in recent years. I visited Vemork power station in 2017, where there was in addition to the industrial and war history of Ryukan, an exhibition of photos and stories of the ‘Tyskejenter.’ Poor girls – there was no value in booking an appointment at the hairdresser’s salon after the 9th May 1945.

Norway had a thorough de-Nazification and rehabilitation programme after VE-Day. The worst offenders such as Vidkun Quisling were rightly executed, but these cases were relatively few in number. Norway is a Christian country, so follows the fine principle of Forgiveness and Redemption that Jesus taught us. Besides, they needed everyone to get the country back on its feet, especially rebuilding all the towns destroyed in the North.

Reading about these stories of people who supported Nazi Germany in WWII has made me appreciate even more those who did choose to join the resistance to occupation: in the darkest years of the war for the allies – between 1940 and 1942 – such resistance would have been an act of the most profound faith in eventual allied victory and liberation, especially in the face of German propaganda… I’m sure many young Norwegian men, ashamed of their country’s defeat in 1940, would have been encouraged to join the ‘Anti-Bolshevik Crusade’ by the posters depicting the Viking next to the Norwegian SS Legion soldier, if the Resistance hadn’t claimed their loyalty in time.

“Så vi vant vår rett!!” 🇳🇴✌️

That was a very well written, informative and nuanced piece. Thank you.

Quisling was pro Norway a nationalist and a patriot. He was not tried and executed. He was murdered.

Germany was sandwiched between a British Empire on one side who wanted them out as a trade competitor and the Bolsheviks in the East on the other side. Quisling understood exactly what was happening. ‘Nazi’ is an applied slur term.