Streaming now on Netflix, the movie is a chilling dramatisation of the 2011 terror attacks and the struggles of the survivors. Here's what to expect, and whether you should watch it.

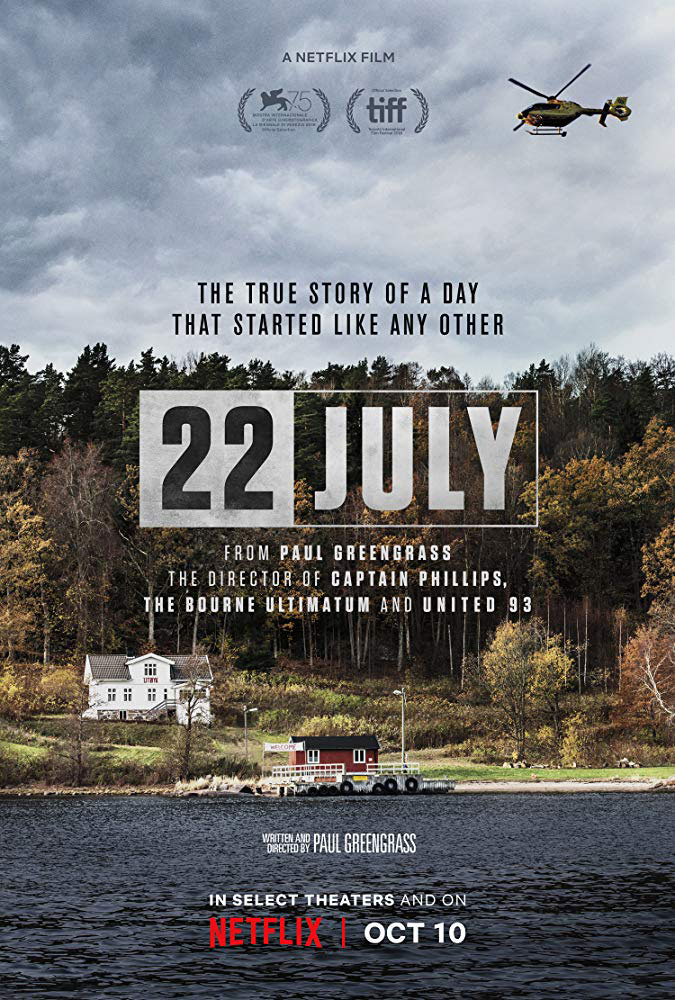

The Netflix movie 22 July is the work of British director Paul Greengrass, a filmmaker with a long history of telling harrowing, real-world stories.

His previous films Bloody Sunday and United 93 are known for their emotional intensity and documentary-style realism, traits that carry through unmistakably into 22 July.

For this project, Greengrass spent considerable time speaking with survivors, victims’ groups, investigators and Norway’s then–Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg.

His stated aim was to handle the events with sensitivity and respect while still confronting audiences with the stark reality of what happened.

The Events of 22 July, 2011

I was in two minds about whether I even wanted to watch the movie, given that what happened that day will stick with me for the rest of my life.

I'd been living in Oslo for just a couple of months and was still getting to know the city. Just an hour or so after I had walked home through the Government quarter, a bomb exploded outside the Prime Minister’s offices, killing eight people and ripping through the heart of Norway’s political centre.

At first, no one knew the scale of what had happened. As sirens echoed through the city, early news reports focused almost entirely on the bombing. It took some time before the true horror began to emerge.

A couple of hours later, reports surfaced of gunfire on Utøya, a small island around 25 miles outside Oslo.

At first, it seemed impossible that the two events could be connected. Utøya was home to the AUF’s annual summer camp, attended mainly by teenagers from all over Norway. The idea that someone could target them was unthinkable.

But related they were. After setting off the bomb, Anders Behring Breivik travelled to Utøya dressed as a police officer. Over the next 72 minutes he murdered 69 people, most of them teenagers, and injured dozens more.

Some drowned trying to swim to safety; others hid under beds, behind rocks, or in the dense forest.

The attack, and the subsequent trial, shook Norway to its core. A country that prided itself on openness, trust and dialogue was suddenly forced to confront hatred on a scale no one imagined possible.

My Thoughts on the Movie

First things first: it’s long. At 2 hours and 24 minutes, 22 July allows time for a detailed exploration of the events, but it also makes the film a heavy, often uncomfortable watch.

This is not a movie you can take in casually. It demands your full attention and, frankly, a fair bit of emotional resilience.

One thing that surprised me was how quickly the film moves past the attacks themselves. Breivik is apprehended after just 32 minutes. Because the story is so well-known, both in Norway and internationally, this decision makes sense.

The more powerful angle, Greengrass seems to argue, lies in what followed: the survivors’ recovery, the political response, and the question of how a society like Norway confronts violent extremism.

Much of the narrative draws from Åsne Seierstad’s acclaimed book One of Us: The Story of a Massacre in Norway, which delves deeply into Breivik’s background, the lives of his victims, and the far-reaching consequences of his actions. Her influence is clear in the film’s attention to detail, especially during the trial.

It does feel a little odd at first that the entire Norwegian cast is speaking English. But Greengrass made a creative decision to tell the story in a way that would reach a global audience without the barrier of subtitles. Given the political themes and the urgency of the topic, I think this approach works.

Jonas Strand Gravli delivers a heart-wrenching performance as Viljar Hanssen, a teenager gravely injured on Utøya who begins the long road to recovery. His story becomes the emotional anchor of the film.

Anders Danielsen Lie, meanwhile, portrays Breivik with chilling restraint. Anyone who saw footage from the real trial will recognise the unsettling calmness, the calculated responses, and the disturbing desire for control. Lie captures all of it.

What the film does particularly well, at least in my view, is to highlight the difficult moral and political questions Norway faced in the aftermath.

How do you prosecute someone who wants to use the courtroom as a platform? How do you behave as an open society when trust has been shattered? And how do victims rebuild their lives when the cameras move on?

What others have said

Watching his horrendous crime and then grappling with his remorselessness and megalomania (he views the courtroom as a stage for his views) may not be much fun, but it confronts you with one of the most pressing dilemmas of our times: what to do about the rise of the far right—in Europe, sure, but not only there – Vogue

Overall, 22 July sees the victims as a largely anonymous mass. Their personalities are vague; their individuation is near-absent. Shouldn’t that trouble us? If Breivik cares about the substance of what his victims believe, he doesn't show it. Shouldn’t we care? The film’s jittery, omniscient style feels at odds with the way it, like many docudramas before it, focuses on a hero and a villain. Incomprehensible loss is flattened into a comprehensible story – Vanity Fair

When Greengrass positions those words next to a madman who committed a grotesque and violent act, it’s a timely, frightening reminder of the direction Western democracies have gone since July 22, 2011, especially when Breivik warns “there will be others” – news.com.au

I feel Greengrass might have done better just to have concentrated on Lippestad’s story and his self-questioning anguish (or made it about the relationship between lawyer and defendant, like Spielberg’s Bridge of Spies; or else perhaps singly about Breivik’s sinister life history, or about one victim’s courageous recovery, and made of any these the individual key that would unlock the whole drama) – The Guardian

22 July is not an easy film to watch, nor should it be. It asks difficult questions about justice, recovery, and democracy. These are questions Norway is still grappling with more than a decade later.

While not perfect, the movie succeeds in bringing an important and painful chapter of recent history to an international audience.