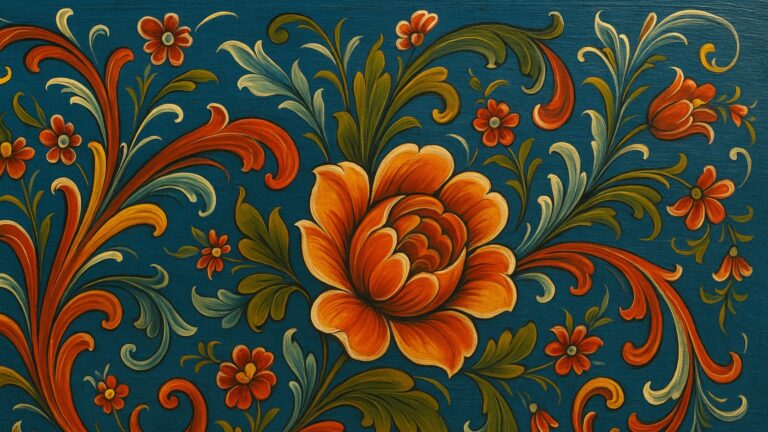

More than just decoration, rosemaling is a vibrant folk art rooted in rural Norway. Once nearly forgotten, this swirling, floral painting style now finds new life in both museums and modern design.

Picture this: you step inside an unassuming 1800s farmhouse in a Norwegian valley, and every surface is painted with wild, swirling flower designs.

The wooden walls, the furniture, even the milk jugs have these psychedelic flowery patterns that look like a folk art version of Versailles’ extravagance.

That’s rosemaling – Norwegian for “rose painting” – and it’s a distinctive Norwegian art form with roots going back to the 1700s. What’s the story behind it and how did it survive to this day? Let’s take a closer look.

The Beginnings of Rosemaling

To understand where rosemaling comes from, you have to look at the interior design trends of the 1700s. If you’ve visited any European palaces or mansions, you know that rich people’s tastes at the time weren’t exactly subtle.

Ceilings were overloaded with ornate plasterwork and gilded moldings, sometimes also elaborate frescoes. Walls had carved panels and shiny gold-leaf reliefs.

This was the height of the Baroque and Rococo era. Although it could only be afforded by the very rich, ordinary people took notice.

Over time, travelling painters and local woodcarvers started borrowing the fanciful designs they saw in churches and manor houses, translating them into painted and carved motifs on wood. Eventually, they reimagined these patterns and made them their own.

They took the swirling scrolls, floral garlands, and intricate ornamentation of palace halls, and simplified them, exaggerated their curves, and painted them in bolder colours that suited rural Norwegian interiors and everyday objects.

Rosemaling wasn’t just about decoration; it was also a way for rural Norwegians to brighten their long winters and put a personal stamp on their homes. This important aspect of Norwegian culture had been born.

The “rose painters” who mastered these designs often worked as travelling craftsmen, moving from farm to farm, sometimes painting entire rooms in exchange for a meal and a warm bed.

In a time when money was scarce, rosemaling provided both artistic expression and a bit of extra income. Each valley or region developed its own twist. Styles like Telemark, Hallingdal, or Rogaland became as distinct as regional dialects.

From Decline to Revival

By the mid-1800s, rosemaling’s golden age was coming to an end. Changing tastes and new influences swept across Norway, and the lavish scrollwork that once brightened rural homes started to feel old-fashioned.

There are multiple reasons for this. The rise of industrialisation brought cheaper, factory-made goods and new materials like wallpaper.

This made it easier (and trendier) for people to decorate their homes in more modern, mass-produced styles. At the same time, economic hardship and mass emigration to America meant fewer families could afford to commission handcrafted art, and many of the old traditions faded quietly into the background.

For a while, rosemaling was largely forgotten. But, as so often happens, it was only when the art began to vanish that people truly started to appreciate what they were losing.

Norwegians began to rediscover and celebrate traditional Norwegian culture and arts at the beginning of the 20th century.

Museums and cultural societies started collecting rosemaled objects, artists and historians studied and preserved regional styles, and soon, classes and competitions were helping to bring the art back to life.

Where to Find Rosemaling

If you’re curious to see authentic rosemaling, some of the best places are Norway’s folk museums. The Norsk Folkemuseum in Oslo, for example, displays historic rosemaled furniture, trunks, and entire rooms decorated in classic styles.

In Telemark the Heddal open-air museum is another prime spot for viewing traditional farmhouse rosemaling as it existed in the 18th and 19th centuries. The artform can also be found in other museums, community centres, and churches so do check with the local tourist office no matter where in the country you end up.

You don’t have to stick to museums, though. Norway’s Husfliden stores, found in many towns and cities all over the country, are a reliable place to find hand-painted rosemaling for sale.

These stores are worth a visit in their own right if you’re interested in other traditional arts and crafts – notably the bunad or traditional Norwegian dress.

Otherwise, you can visit the workshops of specific rosemaling artists, such as Unni Marie’s Rosemaling in Vindafjord, near Haugesund.

Local craft fairs and Christmas markets are also a good place to look if you visit at the right time of year. For those outside Norway, the tradition is alive among the Norwegian diaspora, especially in the United States.

Museums like Vesterheim in Iowa offer rosemaling classes and sell original pieces online and in their gift shop. In places with large Scandinavian communities, you might stumble upon rosemaling items at festivals, folk art shows, or specialty shops.

It’s also worth noting that Norway isn’t the only country with a tradition of decorative folk painting. Sweden, for instance, has its own version called kurbits, with its own colourful, fantastical style found especially in Dalarna.

If you want to acquire a piece, remember: real, hand-painted works are time-consuming to create and priced accordingly. If you’re on a tighter budget, souvenir shops and online stores can sell you a mass-produced item featuring rosemaling designs.

Rosemaling Remains Alive Today

Today, rosemaling is far from a lost art; in fact, it’s very much alive and evolving. Artisans, hobbyists, and even a new generation of designers keep the tradition going.

In Norway, artisans continue to practice and teach this traditional art form, ensuring its transmission to new generations. Institutions like the Raulandsakademiet in Telemark offer courses where students can learn traditional techniques, from mixing paints to mastering the characteristic C- and S-shaped brushstrokes.

Contemporary artists are also reimagining rosemaling, blending classic motifs with modern themes. This is on full display in Trondheim’s new contemporary art museum, PoMo.

Housed in a restored early-20th-century post office, the museum features a reading room decorated with a playful, contemporary interpretation of rosemaling.

Dutch artist duo FreelingWaters painted the A-frame ceiling using rosemaling-inspired brushwork, but instead of the usual scrolls and flowers, their motifs are drawn from local nature and Nordic folklore.

Rosemaling has also inspired international artists. In Stavanger, for example, Portuguese artist Add Fuel (Diogo Machado) created a large-scale work that fuses Norwegian rosemaling with his own roots in Portuguese azulejo tile design.

His mural overlays traditional Rogaland rosemaling patterns with the geometric, repeating forms of southern European tiles. It can be viewed at Stavanger airport.

Across the Atlantic, Scandinavian cultural centres host rosemaling workshops and events, such as the Scandinavian Cultural Center at Pacific Lutheran University in Tacoma, Washington, which offers year-round programming in Scandinavian folk art, including painting classes.

Contemporary artists like Tara Austin push the boundaries of the art, applying them to unexpected materials such as leather, glass, and even electric guitars.

Sometimes she experiments with the motifs themselves, modernising colours or playing with scale, but the heart of rosemaling’s swirling lines and floral energy always remains.

Thanks for this article! I just returned from a rosemaling study tour in Norway that was sponsored by Vesterheim – most of us on the tour are rosemaling in the US. In addition to visiting many of the folk museums, we met several contemporary rosemalers who are keeping the art alive and giving it new expressions: Geir Kåsastul, Anne Hesvik, and Mona Stenseth. It was exciting to see their work and hear them talk about the future of rosemaling.